Meet the Vaux's Swift

The Vaux’s Swift was described by John K. Townsend in 1893. He named it after his friend William S. Vaux who was at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. And, just to settle the matter up front….according to accounts, Vaux pronounced his name “Vox”, therefore “Vaux’s Swift” rhymes with “foxes swift.”

Vaux’s Swifts adhere their stick nests to the sides of hollowed out snags in old forests, and in chimneys in towns across the Pacific Northwest, from the Yukon to the mountains of coastal and central California. After the nesting season, adults and young migrate to Mexico and Central America to overwinter. (Separate subspecies are permanent residents in Mexico and Central America.) They are declining at a rate of about 2% per year according to Breeding Bird Survey data. That, combined with their spectacular spring and fall stagings as they pass through our northwestern states, is what draws so many of us to this species, why they become school mascots, why old chimneys are reinforced rather than demolished, and what inspired a coalition to be built around its conservation.

Vaux’s Happening

Three Audubon chapters in the Puget Sound area (Seattle, Eastside, and Pilchuck) banded together in 2007 to save the old brick chimney at Frank Wagner Elementary School from demolition. This chimney was one of only two well-known Vaux’s Swift communal migratory roost sites in Washington state. Vaux’s Happening was an outgrowth of this coalition. Our focus soon included an attempt to locate and monitor all significant Vaux’s Swift roost sites in North America in both spring and fall, which is no small task. Our mission is to promote the conservation of migrating Vaux’s Swifts by raising awareness of their spectacular roosting events at a limited number of large trees and old masonry structures on the Pacific Flyway. By doing so, we hope that more people will come to care about its conservation, and preserve the chimneys and old growth that these birds rely upon. The project has had exceptional participation over the last 24 migrations, and we have learned so much about the species and critical features of their communal roosts. This is truly citizen science. Here are some highlights:

- The project has involved hundreds of people monitoring swifts, with low turnover

- The volunteers have made 12,770 observations over 24 migrations

- They have counted (not estimated) 14,845,442 individual Vaux’s Swifts going to roost

- Counts took place at 176 roost sites

Our data suggest that about 4 times as many swifts head south in the fall relative to the number that return the following spring. This suggests migration and over-winter survival take an annual toll, or, migration routes and roosting habits are different in the spring and fall, or both. There is some evidence that routes north and south are, in fact, different; the central California roosts that are lucky to host 100 swifts per day in April and May can be totally overwhelmed with 20,000 to 50,000 birds in any night in September. eBird reports document over a thousand of Vaux’s Swifts in the Kern River Valley at the southern end of the Sierra Nevada in April and May, but in September they are much less common.

To date, the northernmost roost discovered is about as far northwest as you can go in British Columbia. David Fraser documented 30 Vaux’s Swifts on July 15, 2010 and 20 individuals the next day at Petroglyph Island with the note, “group of swifts associated with the very old cottonwood stand on Petroglyph Island. This species is regular at this location.” And far to the south, 20,000 Vaux’s Swifts traditionally returned to the old sugarcane chimney at Finca El Zapote in Guatemala in December. This wintering site was first described in a 1928 German Scientific paper and according to the owner has been continually active. The adjacent Volcan de Fuego was also once described as continually active, however, beginning in 2017 a series of eruptions have apparently caused the swifts to abandon this site.

Every migration, 90% of our totaled recorded swifts come from only about a dozen roost sites. These sites are about 50 to 150 miles apart. We believe that is how far they migrate in one day. For example, swifts leaving the Chapman Elementary School chimney in Portland may spend that evening 100 miles to the south in Eugene at the Agate Hall chimney. Or, they might travel much further; only additional research will tell us.

Conservation of Chimneys

In the absence of old growth forests, Vaux’s Swifts have taken to old, unused brick chimneys that date back to the 1940’s. More modern chimneys are lined and don’t provide the bumps and edges that old masonry provides for the clinging birds. The focus of Vaux’s Happening has been to save as many of these old structures as possible from being demolished. To save the chimney at Wagner Elementary, representatives from each of the Audubon chapters successfully appealed for state funds. (It may have helped that then chairman of the Capital Budget Committee, Hans Dunshee, actually attended Monroe Wagner School.) With $100,000 in funds, the group began seismic retrofits to stabilize the chimney roost. This chimney may now be the most significant Vaux’s roost in North America, hosting as many as 26,500 in the fall (as counted in one night in 2010), and 18,600 in the spring (as counted in one night in 2018). Now there is a statue in downtown Monroe proclaiming the Vaux’s Swift to be Monroe’s Official City Bird! Conservation success!

Vaux’s Swift statue in Monroe, Washington (Credit: Cathy Clark)

In Albany, where a chimney could not be saved, we erected an alternative to lure the birds to roost. Unfortunately, it remains unused today. In another project, a chimney in Rainier, WA that was sealed off 28 years ago was re-opened in the spring of 2019. The swifts adopted this chimney during their fall 2019 passage (17,889 in one night), and also the following spring (12,090 in one night). Truly impressive numbers and gratification for this endeavor.

The Science

Why the swifts are so determined to come together in such large numbers is part mystery and part mystery solved. One mystery is that we still do not know just how they dissipate heat generated during flight from their nearly continuous flapping. They might possess unique feather structure, feather arrangement, and physiology to allow for heat dissipation. We do believe that they may be relatively ineffective at conserving body heat when they are not flying, and that is why they mass together in chimneys and trees during migration and in the winter. These structures retain heat during cool nights.

To learn more, we placed remote temperature recorders inside the Wagner roost. We expected that if there were few or no birds, the temperature inside might be a couple of degrees warmer than outside. Instead we found that the temperature inside the chimney was up to 25 degrees F warmer than outside. The Vaux’s Swifts press against the bricks all night long, absorbing the latent heat. We now have temperature readings from nearly half of our major roosts and each one has yielded a large difference between inside and outside temperatures overnight. The Chapman chimney in Portland is so many bricks thick that once it heats up in August it maintains a nearly constant temperature for 24 hours a day, like a long brick oven set on “warm.”

In 2010 we installed two live-streaming cameras at the Wagner chimney, one looking across the chimney opening and another looking down inside the chimney. Here are some highlights of what we learned:

- Crows like to prey on swifts as they exit chimneys in the morning. It is possible to discourage this predation with slinkies, bird spikes, and an aluminum sheet wall surrounding chimney openings. These deterrents are visible in this live-stream.

- The swifts enter the roost at the rate of up to 100 or more birds per second, while they are hard-pressed to exit faster than 12-15 birds per second.

- Bedtime is at sunset, unless there is rain. The birds will use the roost to avoid heavy rain.

- They take flight after their insect prey has begun flying. The time they exit varies a great deal but averages two hours after sunrise. (It is very unusual for them to leave before sunrise. We suspect those that do have a big travel day planned and a full “tank” of bugs.)

- They do not migrate or hunt in the dark. Infrared video has never caught one going in or coming out of a roost much more than an hour after sunset.

- The Vaux’s do not seem to enter a state of torpor in the roost; in fact, they are active and make lots of noise all night long. The sounds they make in the roost are different from their sounds on the wing. (See video of the Wagner roost here.)

- The colder it is, the closer together the swifts huddle, and as the evening gets cooler the swifts migrate further down into the chimney.

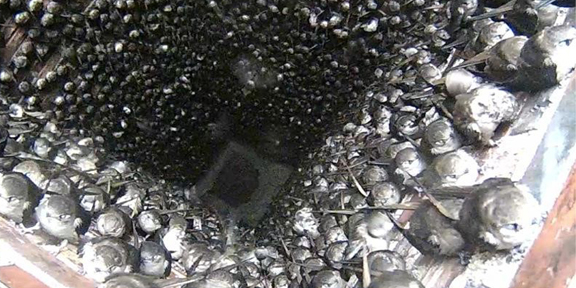

- The Vaux’s Swift body length and normal masonry spacing is such that a row of swift chins overlaps the tails and rumps of the row above.

- We have never witnessed swifts acting aggressively towards each other in the roost.

- Wagner has roosting swifts all summer long, but not one nest in the last ten years.

Vaux’s Swifts stacked head-over-tail in the Wagner chimney. (Credit: Larry Schwitters)

The Future

The people involved with Vaux’s Happening will continue to document and save as many of these critical stopover sites as possible. Vaux’s Swifts, after all, are tremendous bird ambassadors, and an entrée to conservation for thousands of people. Each year the grassy slope overlooking the Chapman Elementary School playing fields, with a wide-open view of the reinforced chimney above, provides a stadium-like atmosphere for the hundreds of festive spectators that gather daily during late August through September (socially-distanced this year, please). Portland Audubon is onsite, counting and providing outreach. Similar scenes occur in Eugene at Agate Hall, at the Umpqua Valley Center in Roseburg, Hedrick Middle School in Medford, and the Riverside Church in Rainier, Oregon, and of course, at the Wagner chimney in Monroe, Washington. As September arrives, consider visiting one of these roosts to enjoy the spectacle.

If you would like to join the Vaux’s Swift conservation effort or become involved with Vaux’s Happening, contact Larry Schwitters at leschwitters@me.com.