The 2024 Taxonomy Update is: COMPLETE.

At this stage, all major taxonomic revisions are done. Small database changes may continue for the next several weeks.

Taxonomy webinar: In related news, our taxonomy team (Pam Rasmussen, Marshall Iliff, and Shawn Billerman) will give their annual What’s New in Avian Taxonomy webinar on 14 November at noon ET. At that time, we’ll again leave the site open from 14–18 November to encourage more exploration. Registration link for the webinar is here. The webinar will be in English.

We have now completed the process of updating records in eBird. This includes your My eBird lists, range maps, bar charts, region and hotspot lists. Data entry should be behaving normally, but you may notice unexpected species appearing on eBird Alerts as eBirders continue to learn the new taxonomy (this issue will diminish with time). If you still see records appearing in unexpected ways please write to us.

If you use eBird Mobile, we recommend installing pack and app updates immediately as they become available. This will make sure you have the most up-to-date lists for reporting.

Read on for more information about what’s changed. For a complete list of all taxonomic changes, check out the 2024 eBird Taxonomic Update page.

It’s Taxonomy Time!

“Taxonomy” refers to the classification of living organisms (as species, subspecies, families, etc.) based on their characteristics, distribution, and genetics. There are multiple taxonomies for birds around the globe. Projects at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology—including eBird, Merlin, Birds of the World, and the Macaulay Library—use the eBird/Clements Checklist of Birds of the World, or eBird/Clements Checklist for short.

Our understanding of species is constantly changing. Every year, some species are “split” into two or more, while others are “lumped” from multiple species into one, as we gain a better understanding of the relationships between birds. The eBird/Clements Checklist is updated annually to reflect the latest developments in avian taxonomy. “Taxonomy Time” is an opportunity to celebrate the many scientific advances in ornithology made over the past year—some of them thanks to your eBird data!

As part of this process, we revisit all 1.8 billion observations in the eBird database and update them to reflect recent splits, lumps, additions of new species, changes to scientific names, taxonomic sequence, and more. Wherever possible, and in almost all cases, we update your records for you. Not having to worry about name changes or species splits is one of the benefits of being an eBirder. It’s our way of thanking you for contributing to our understanding of bird populations. Below are some highlights from this year’s Taxonomy Update, which includes 3 newly-recognized species (one is newly-described), 141 species gained because of splits, and 16 species lost through lumps, resulting in a net gain of 128 species and a new total of 11,145 species worldwide.

What Changed in 2024

Our 2024 update includes 3 newly-described species, 141 species gained because of splits, and 16 species lost through lumps, resulting in a net gain of 128 species and a new total of 11,145 species worldwide.

For a complete list of all taxonomic changes, check out the 2024 eBird Taxonomic Update page.

Herring Gull

Herring Gull (Larus argentatus) will be split into:

- American Herring Gull (Larus smithsonianus)

- European Herring Gull (Larus argenteus)

- Mongolian Gull (Larus mongolicus)

- Vega Gull (Larus vegae)

As part of this split, more than 7 million eBird observations will be revised. In terms of the total number of impacted records, this is the biggest taxonomic revision in eBird history! Anyone who has previously reported “Herring Gull” will see their observations appear as “Herring Gull (American)”, “Herring Gull (European)”, “Herring Gull (Mongolian)”, and/or “Herring Gull (Vega)” until taxonomy updates are complete in late October.

This split was first proposed more than two decades ago and a growing body of evidence suggests geographically separate populations of large-bodied, white-headed gulls do not interbreed as extensively as once thought. American Herring Gull is the expected species in the Americas and European Herring Gull is the expected species in Europe. Mongolian Gull breeds across Mongolia and northeastern China, and Vega Gull rounds out the distribution in northern Siberia.

Adult American and European Herring Gulls are differentiated by subtle plumage characteristics that may be hard to perceive in the field, but immature birds are more distinctive (e.g., mostly dark tail in American Herring) and can be identified consistently within expected regions. Adult Vega Gulls, by comparison, have darker gray mantles, an indistinct “string of pearls” wing pattern (resembling Slaty-backed Gull) and more heavily streaked head in winter plumage. Immature Vega Gulls resemble European Herring more than American Herring, especially in the tail pattern. Adult Mongolian Gulls have faintly to entirely unstreaked heads in winter and may show a grayish or yellowish tinge to the legs in breeding plumage; immatures are quite distinctively pale.

Note some degree of range overlap between Vega and American Herring Gull in the summer and Vega and Mongolian gull in the winter. ‘Slash’ options such as Vega/Mongolian Gull will be available.

House Wren

The iconic House Wren (Troglodytes aedon) is about to become seven. Two species are found on the American continents, overlapping in southern Mexico:

- Northern House Wren (Troglodytes aedon)

- Southern House Wren (Troglodytes musculus)

Five additional species are endemic to individual Caribbean islands:

- Cozumel Wren (Troglodytes beani)

- Kalinago Wren (Troglodytes martinicensis)

- St. Lucia Wren (Troglodytes mesoleucus)

- St. Vincent Wren (Troglodytes musicus)

- Grenada Wren (Troglodytes grenadensis)

Four of these wrens are named for the islands where they are found. Kalinago Wren refers to the Kalinago people, the main indigenous community of the Lesser Antilles prior to European colonization and one of the last remaining pre-Columbian cultural groups in the Caribbean. The Kalinago Wren historically inhabited the islands of Dominica, Martinique, and Guadeloupe. Today, this species can only be found in Dominica. The AOS and eBird/Clements Checklist is grateful to Kalinago Chief Lorenzo Sanford and the Kalinago Council for allowing the use of ‘Kalinago’ in the English name of this newly recognized species.

Notable Splits

The below splits are highlighted because they affect widespread, familiar species and have particularly broad implications across many continents. Additional details about the distribution, field marks, and vocalizations of these splits and various subspecies groups will be available soon.

Cory’s Shearwater—split into Cory’s Shearwater (Calonectris borealis) and Scopoli’s Shearwater (C. diomedea); visit our article on Cory’s/Scopoli’s Shearwater for more information about how this split could impact your eBird Life List.

Barn Owl—An overdue three-way split into Western Barn Owl (Tyto alba) of Europe, Africa, and western Asia; Eastern Barn Owl (Tyto javanica) of South and Southeast Asia and Australasia; and American Barn Owl (Tyto furcata) of North and South America. Other taxonomies have recognized this split for some time. Barn Owl vocalizations are a complex array of sounds that mostly sound like raspy screeches to our ears, but probably mean a lot more to the owls. If we had to guess, we’d predict more Barn Owl splits in the coming decade, especially in the Americas. Decoding their screeches will be a key factor in these decisions.

Red-rumped Swallow and Striated Swallow—A complicated revision here, since Striated Swallow (Cecropis striolata) is lumped with Red-rumped Swallow (Cecropis daurica), and then the species is re-split in three ways:

- European Red-rumped Swallow (Cecropis rufula), breeding in Europe and northern Africa east to Afghanistan and northern India

- African Red-rumped Swallow (Cecropis melanocrissus) of sub-Saharan Africa

- Eastern Red-rumped Swallow (Cecropis daurica), including both the resident subspecies formerly considered Striated Swallow and migratory taxa of northern and northeastern Asia

New identification challenges will arise, particularly with vagrants, as well as in areas of overlap: sub-Saharan Africa (where European and African Red-rumped co-occur for part of the year); and central Asia and the Middle East (the contact zone between European and Eastern Red-rumped Swallows) .

Rock Martin—This year brings a three-way split to this widespread African swallow in the genus Ptyonoprogne:

- Pale Crag-Martin (P. obsoleta) occurs in the Middle East and Northern Africa (mostly north of the Sahara Desert)

- Red-throated Crag-Martin (P. rufigula) occurs in western, central, and eastern Africa

- Southern Crag-Martin (P. fuligula, sometimes known as Large Rock Martin)

Red-throated Crag-Martin comes in contact, at least seasonally, with the other species at the northern and southern extremes of its ranges, so new identification challenges will emerge, especially in central Africa where wintering Eurasian Crag-Martins might also be found. Since the northernmost form being split has always been known as Pale Crag-Martin—and since the genus Ptyonoprogne has two other species known as Crag-Martin—we now use Crag-Martin across the entire genus of these rock-nesting, spotty-tailed swallows.

Brown Booby—Cocos Booby (Sula brewsteri and S. etesiaca) is split from Brown Booby (S. leucogaster). Cocos Booby occurs mostly on the Pacific coast from northern South America to southern California, and increasingly in Hawaii and more widely in the Pacific. Brown Booby includes all Atlantic and Indian Ocean populations (S. l. leucogaster), plus subspecies plotus of the Indian and tropical Pacific Oceans.

Both species come into contact in the Hawaiian Islands, and the lack of hybridization there was a major reason for the split. “True” Brown Booby has yet to be found near the Pacific coast, but will be one to watch for, since all taxa in this group seem to be expanding their ranges as the oceans warm.

Major “Megasplits”

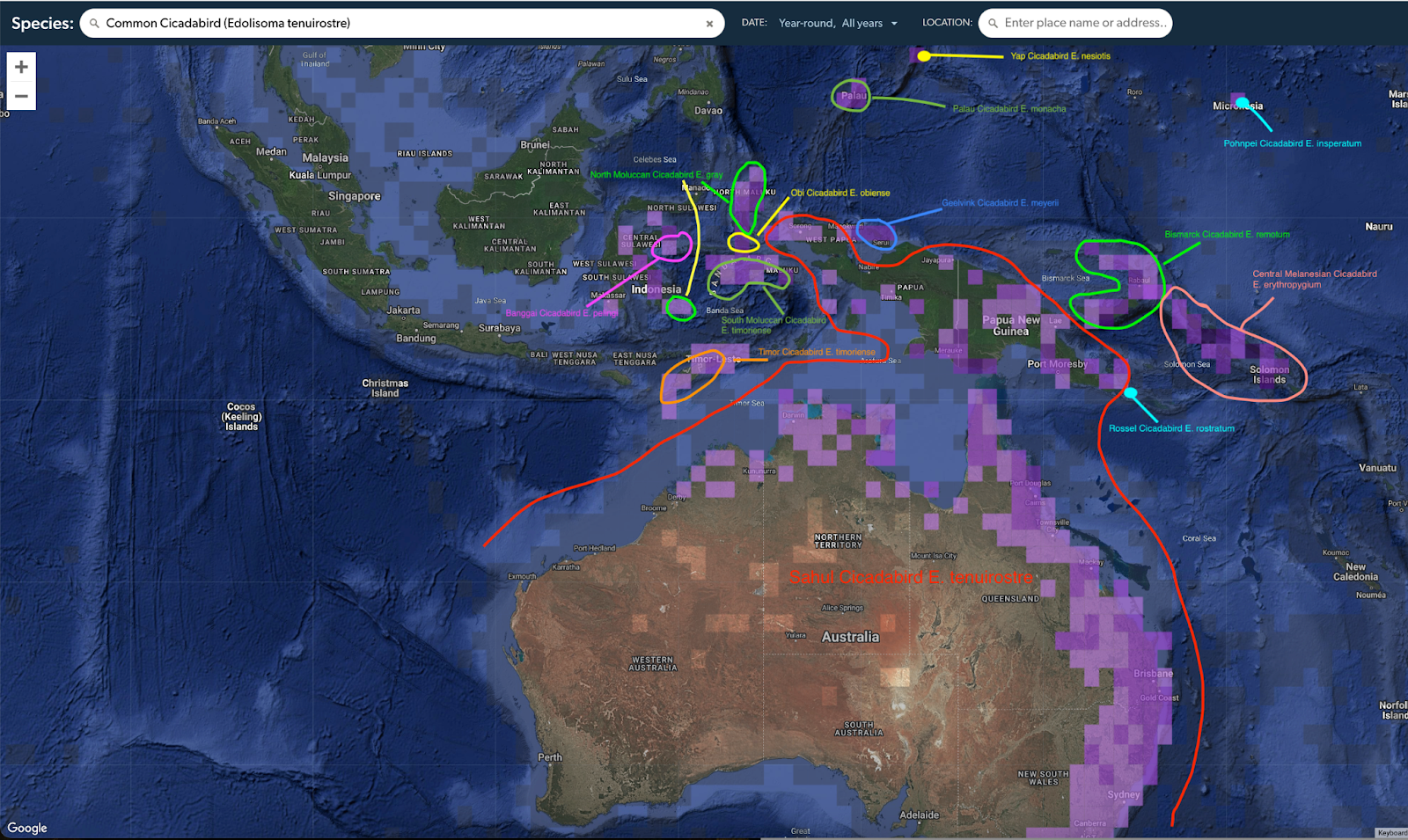

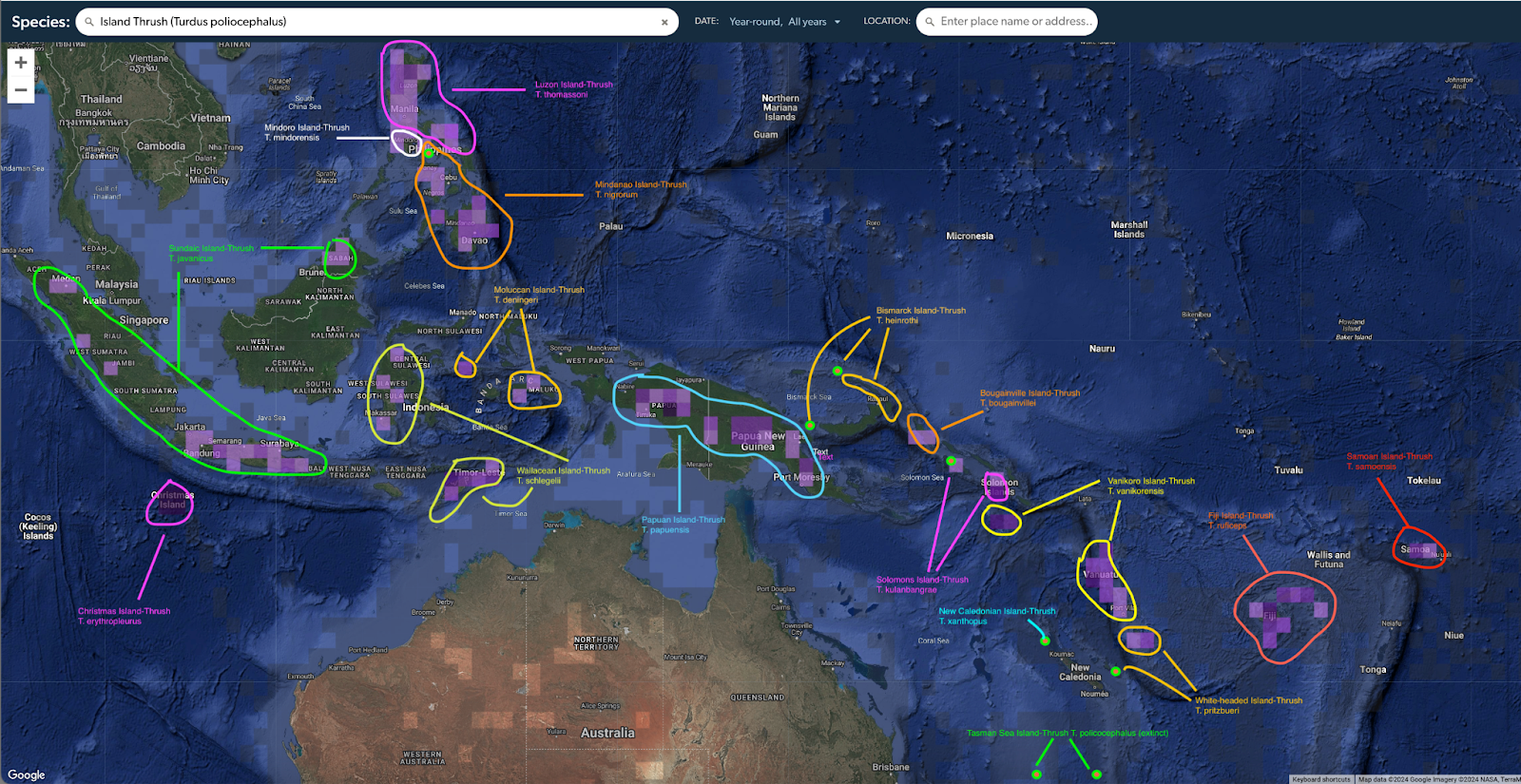

Of the 128 new species recognized through splits, fully 22% (29) of those are because of splits within two species: former Common Cicadabird (Edolisoma tenuirostre) and former Island Thrush (Turdus poliocephalus).

The remarkably widespread range and diverse plumage variation within Common Cicadabird (Edolisoma tenuirostre) has long been known, but only through recent fieldwork in Australasia has enough information on plumage, voice, and other characteristics been compiled to allow for a global revision. In their best attempt at integrative approach, the AviList Committee has proposed a new arrangement of 13 species:

- Timor Cicadabird (Edolisoma timoriense)

- Pohnpei Cicadabird (Edolisoma insperatum)

- Palau Cicadabird (Edolisoma monacha)

- Yap Cicadabird (Edolisoma nesiotis)

- Bismarck Cicadabird (Edolisoma remotum)

- Central Melanesian Cicadabird (Edolisoma erythropygium)

- Geelvink Cicadabird (Edolisoma meyerii)

- Banggai Cicadabird (Edolisoma pelingi)

- Obi Cicadabird (Edolisoma obiense)

- North Moluccan Cicadabird (Edolisoma grayi)

- South Moluccan Cicadabird (Edolisoma amboinensis)

- Rossel Cicadabird (Edolisoma rostratum)

- Sahul Cicadabird (Edolisoma tenuirostre)

In addition, subspecies edithae is transferred to Sulawesi Cicadabird (Edolisoma morio).

Island Thrush (Turdus poliocephalus) was previously considered to have the most subspecies of any bird in the world (our 2023 taxonomy had 52 subspecies!). Perhaps not surprisingly, its immense diversity of plumage across a broad range of islands—many of which are well-known for their endemism—meant that the bird formerly known as “Island Thrush” was in fact a complex of diverse species. New research has quantified the genetic and plumage diversity and allowed for a broad reassessment. Up to 23 different species were potentially considered for this 17-way split, so additional splits are still possible.

Congratulations to anyone who has birded widely in this region for all their new thrush AND cicadabird Life Birds!

A New Tityra

One of the fun updates this year is the promotion of White-tailed Tityra (unrecognized species) (Tityra leucura [unrecognized species]) to full species status as White-tailed Tityra (Tityra leucura). This bird was one of South America’s remaining mysteries. A single specimen was collected in 1829 near Porto Velho, Brazil. Then, in 2006, one of Brazil’s foremost experts observed one, but no photos were taken. The South American Classification Committee reviewed the case, noting the fully white tail and smaller size compared to other tityras. However, because only one specimen had ever been found—and since tityras are usually rather conspicuous—some members thought it might just be an aberrant Black-tailed Tityra.

On 8 September 2022 Bradley Davis, a longtime reviewer and coordinator for eBird in Brazil, was finally able to get photos and even video of the mysterious tityra. He observed that it was smaller and moved quietly in the treetops, unlike other tityras. This was the proof needed to confirm the species’ existence after 195 years of uncertainty—although the species still awaits official SACC approval. Much remains to be learned about this species, including its vocalizations, its habits, and the true extent of its range.

Three Redpolls Become One

In addition to the species splits above, one notable “lump” this year is of Common, Hoary, and Lesser Redpoll into the mononymous “Redpoll” (Acanthis flammea). This is based on recent genetic evidence that differences in appearance between populations are controlled by a single shared “supergene”, and populations are otherwise lacking in genomic distinctiveness or evidence of prolonged isolation.

‘Accipiter sp.’ No More

Identifying hawks in the genus Accipiter is a well-known problem worldwide, whether it involves distinguishing Eurasian Sparrowhawk from Eurasian Goshawk in Eurasia; Crested Goshawk from Besra in Southeast Asia; African Goshawk from Shikra in Africa; or Sharp-shinned from Cooper’s Hawk in North America.

In recent years, research has shown that Accipiter is not a monophyletic genus, meaning its members are not all closely related. This year the long-anticipated breakup of the genus has finally occurred.The identification challenges will remain, but we are hoping it will be helpful to learn the characteristics and behaviors—especially flight displays—that are unique to the new genera.

- Crested Goshawk and Sulawesi Goshawk move to Lophospiza—known from their flight displays with puffed up undertail coverts;

- Cooper’s Hawk, Eurasian and American Goshawk, and their close relatives (Gundlach’s, Bicolored, and Chilean Hawks in the Americas; Black and Henst’s Goshawks in Africa; and Meyer’s Goshawk in New Guinea) move to Astur—highlighting their hefty size, slow languid wing flaps during display, and call similarity;

- African Goshawk and the closely related Chestnut-flanked Sparrowhawk move to Aerospiza—are known for vocalizing during early morning display flights with slow flaps, puffed out undertail coverts, and swooping flights;

- A large number of smaller hawks from Africa, Asia, and Australasia move to Tachyspiza—united by their small size and snappy flaps in flight and their propensity not to perform flight displays.

This leaves just six true Accipiter: Eurasian Sparrowhawk in Eurasia; Ovambo, Madagascar, and Rufous-breasted Sparrowhawks in Africa; Gray-bellied Hawk in South America; and Sharp-shinned Hawk, in North and South America.

While Accipiter sp. will no longer be available as a reporting option, birders will still have ‘slash’ options for the most similar species, including:

- Besra/Japanese Sparrowhawk

- Collared Sparrowhawk/Brown Goshawk

- Eurasian Sparrowhawk/Eurasian Goshawk

- Cooper’s Hawk/American Goshawk

- Crested Goshawk/Besra*

- Levant/Eurasian Sparrowhawk*

- Sharp-shinned/Cooper’s Hawk*

* note that the last three pairs are in different genera.

If you really don’t know, and don’t have an appropriate slash, you will have an equivalent option to Accipiter sp.: Accipitrine hawk sp. (former Accipiter sp.).

Reviewing your records for changes

Where taxonomic changes affect your observations, we will do our best to assign them to the correct new species. However, this is not always possible, and in some cases your records may be updated to a ‘spuh’ (e.g., sand-plover sp.) or ‘slash’ (e.g., Western/Eastern Cattle Egret) instead. With the recent improvements around exotic species handling, it is now very easy to see all of your reports of a ‘spuh’ or ‘slash’ under Additional Taxa on your eBird Life List. Please check those in the weeks after the update to make sure your records have been moved as expected.

Even More Updates

This year’s update—as with other recent updates in 2021, 2022, and 2023—has an unusually large number of changes, including updates to scientific names, as well as splits and lumps. Each of the recent updates has represented a gradual movement towards the consensus taxonomy being developed by the AviList Committee (formerly referred to as WGAC). Representatives from eBird/Clements, BirdLife International, IOC, AOS-NACC, and SACC, as well as other experts in the field, have been collaborating since February 2021 to collect and review information on all cases of taxonomic disagreement between the major world lists represented in the group (i.e., eBird/Clements, IOC, BirdLife, AOS-NACC, and SACC). Your observations, photos, and especially audio recordings have been tremendously useful in these analyses!

This initial review is now complete at the species level (subspecies remain to be reconciled), and while not all changes are represented in the eBird/Clements list, we are pleased to note that we expect the AviList checklist of world birds to be published in 2025 and we hope and expect the eBird/Clements checklist to follow that new list for taxonomy and scientific nomenclature going forward.

Stay tuned for the more complete list of eBird/Clements changes for 2024, coming in the latter half of October!