Learning the Secrets of the Secretive Black-Billed Cuckoo

If you live in Montana, hearing the staccato call of the Black-Billed Cuckoo is a rare treat. Seeing one is even more extraordinary. This cryptic species is regionally scarce and vocalizes infrequently. Their populations have declined nationally by an astounding 67% from 1970 to 2019 based on Breeding Bird Survey data – making them increasingly hard to find and a priority to document.

Black-billed Cuckoos have graceful curving bills and bright red eyes, and prefer skulking in dense thickets to singing in the open, making them a prized sighting for birdwatchers. They are found primarily in deciduous forests and dense thickets in the northeastern United States. Most observations in Montana have been along large river floodplains in the eastern part of the state where cottonwood galleries line the rivers. But only a few are observed each year, making it difficult for wildlife biologists to confirm their distributions and habitat preferences in Montana. To complicate matters, their populations are thought to be irruptive, cycling locally with insect outbreaks of tent caterpillars, webworms, and cicadas. In fact, cuckoos have evolved the ability to eat caterpillars considered unpalatable by other birds by regurgitating their irritating hairs and spines, along with the cuckoo’s own stomach linings, in pellets, much like an owl. The annual variability in species that are rare, irruptive, and patchy means surveys must be completed for multiple years before cuckoo presence, and ultimately population trends, can be established. Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks lists Black-billed Cuckoos as a species of high inventory need because current monitoring efforts are insufficient to determine their population status or trends in the state.

Anna Kurtin, a graduate student co-advised by Dr. Erim Gomez at the University of Montana’s Wildlife Biology program and Dr. Andy Boyce with the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, knows just how lucky you have to be to hear one. She spent last summer climbing through dense thickets of wild rose and willows along the banks of the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers searching for them. Using the traditional survey method for cuckoos, she broadcast their calls from a speaker in the morning hours to elicit a response, since they rarely vocalize on their own. Among the 27 sites she surveyed over the summer, she only found cuckoos at three.

Since 2012, researchers from the University of Montana Bird Ecology Lab (UMBEL) have conducted annual surveys for cuckoos along with other songbirds that breed in the productive riparian habitats along the Missouri River as it flows through the arid breaks of Montana. “Accessing river habitats in remote areas of Montana is challenging, often requiring boat access and hours of paddling for a single morning survey”, explains Anna Noson, UMBEL research director. “In some years, we’ve heard a few cuckoos calling from patches of riparian vegetation along the river, but in most years we didn’t find any.” And since biologists don’t know all the factors that affect detections, like survey timing and environmental conditions, these observations are insufficient to evaluate the species’ population status or habitat needs in Montana.

Black-billed Cuckoo. Photo by Bo Crees.

Kurtin is using new acoustic technology to help overcome these challenges. While struggling through the undergrowth conducting traditional broadcast surveys last summer, she also strapped 72 acoustic monitors to trees, while project collaborators deployed another 73. “This technology has the potential to dramatically expand our understanding of cuckoos by allowing researchers to “listen” for cuckoos across the entire summer instead of a single morning” says Kurtin. She first became interested in acoustic research while studying how howler monkeys vocally respond to rainy conditions in Ecuador. She then helped the National Park Service deploy acoustic recorders for bats and owls in Arizona and is excited to apply her experience to the elusive cuckoo in Montana. Her research is a collaborative effort, with support from UMBEL, Northwestern Energy, Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks, and the Bureau of Land Management, Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, the UM Charismatic Minifauna Lab, Montana Audubon, The Kitzes Lab at the University of Pittsburgh, American Prairie, and access from tribal and private landowners.

Unlike traditional survey methods, acoustic monitors are not constrained by time and require less specialized training for deployment. However, they come with their own suite of challenges, including data storage and processing. Each acoustic monitor holds approximately 152 hours of recordings after it is collected from the field, and with 145 monitors deployed, this totals up to 918 days of acoustic recordings! With collaborators at the Kitzes Lab at the University of Pittsburgh, Anna Kurtin is working to apply new techniques for identifying bird calls within acoustic recording data using artificial intelligence. “Collaborating with the Kitzes Lab is an exciting opportunity to apply the cutting edge of acoustics research to our project by building a specialized machine learning model to dramatically speed up the time it takes to process this data” says Kurtin. Through a process of training and evaluating this machine learning model, she is developing a streamlined process to pick cuckoo calls out of recordings, turning what would be months of listening to recordings into hours. This methodology also has the potential to be applied across other bird or animal species.

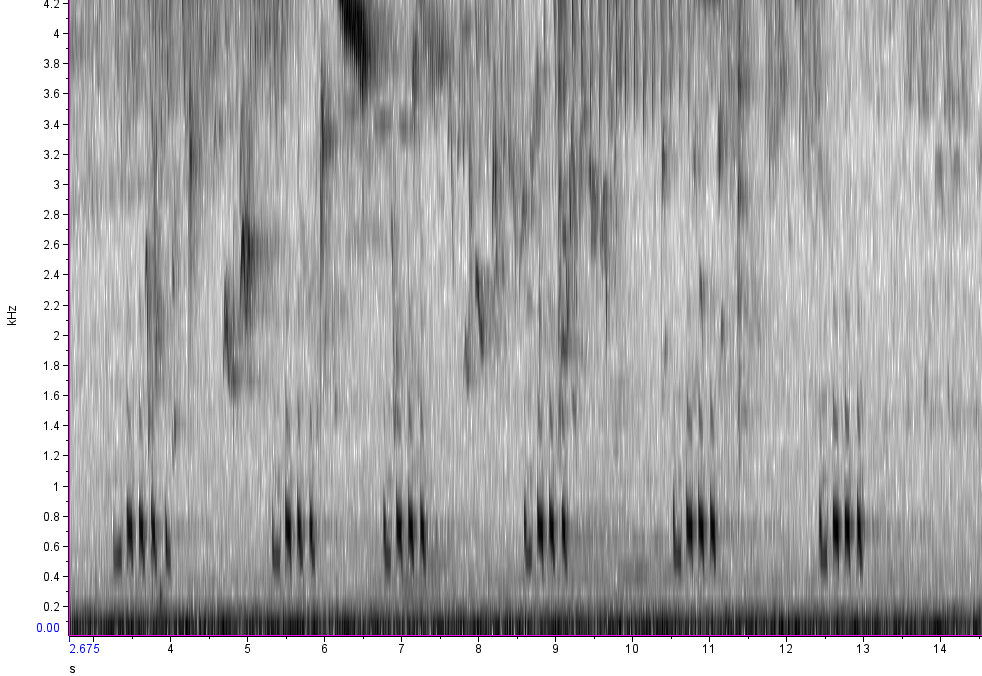

To listen in on Black-billed Cuckoos, biologists use spectrograms, like the one above, which present a visual depiction of the cuckoo’s unique call. A spectrogram is literally the 2-D shape of a sound.

Preliminary results from Kurtin’s graduate research show acoustic monitoring has led to more confirmed cuckoo presence at sites on the Missouri River than traditional surveys, suggesting this new approach is working. Kurtin plans to analyze recordings to determine when cuckoos are more likely to call during the day and when they are most vocal across the summer season. She will also examine habitat conditions at sites where cuckoos are found to fill gaps in our understanding of their habitat use in Montana. Her findings will optimize future monitoring efforts in Montana and lead to a greater understanding of where Black-billed Cuckoos prefer to skulk in Montana – a boon to conservation of the species as well as for birdwatchers hoping to hear their first cuckoo.

Stay tuned for more cuckoo updates!

Although this summer has found Anna busy in the field, she expects to have results to report as early as Spring 2024. Tune in to the Montana eBird News blog for future updates on Anna’s research as she unveils the secrets of Montana’s enigmatic Black-Billed Cuckoos.