Caribbean Birders Take Note: Changes are Upon Us!

How the most recent supplement to the AOU Checklist of North American Birds impacts the way we see and define coots and bullfinches in the Caribbean.

Every year, new ornithological research digs deeper into furthering our understanding of the complex behaviors, distributions, morphologies, and relationships among bird species across the world. As new information rolls in, proposals are made to modify our current classifications of all these species. The North American Classification Committee (NACC) is an official committee within the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) that bears the responsibility of weighing and subsequently incorporating these proposals into the current ornithological taxonomy and nomenclature.

Beginning in 1886, the NACC has published the AOU Checklist of North American Birds that comprehensively catalogues bird species known to North and Middle America. Most recently, their 57th Supplement to this checklist was released in June via the AOU’s peer-reviewed scientific journal, The Auk: Ornithological Advances. Within that supplement, two species well-known to Caribbean birders have undergone important changes, and are discussed below.

Caribbean Coot – Not a Unique Species

The Caribbean Coot (formerly Fulica caribaea) was – until recently – considered to be its own species of coot endemic to the Caribbean Basin (residing in Venezuela as well as the West Indies). It is a regular member of wetland communities where it can be seen swimming on ponds and lakes as well as walking about on the shore.

The Caribbean Coot, with its white shield extending up on to the top of the head, is no longer regarded as a separate species, but rather a sub-species of the American Coot. Enter your sightings in eBird Caribbean as “American Coot (White-shielded).” Photo by Mario Espinosa.

It was historically thought that Caribbean Coots and their very similar appearing congener, the American Coot (Fulica americana), were separate species. As of this year, however, the AOU has decided that Caribbean Coots actually belong to the American Coot species.1 The best evidence for this comes from research on their breeding biology by Douglas McNair and Carol Cramer-Burke.2 It seems that St. Croix Caribbean and American Coots choose mates randomly with no regard for species, implying that there is no reproductive isolation on St. Croix. While occasional hybridization is ok, if the two were actually unique species, birds would have at least some preference (a strong preference, in fact) for breeding with fellow birds from their own species.

Adding to that, the birding community originally thought Caribbean and American Coots could be distinguished by the morphology (size, length) and color of the shields and calluses located on their foreheads. However, that has become….messy. Furthermore, there are no discerning characteristics between their vocalizations.

All this implies that the Caribbean Coot has not actually differentiated from the American Coot enough to be its own unique species.3

Should I Identify and Report “Caribbean” Coots on eBird Caribbean Checklists?

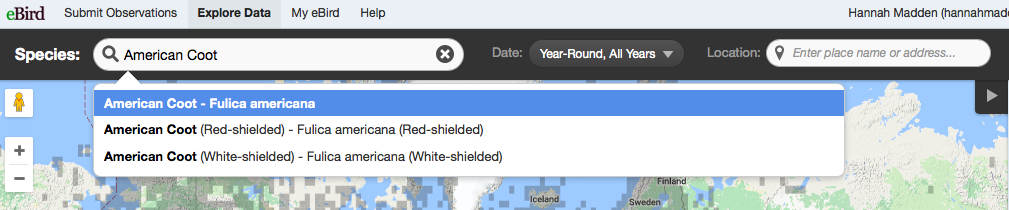

Yes, but no longer as “Caribbean” Coots. eBird Caribbean now has three options when reporting coots belonging to the Caribbean/American Coot complex: “American Coot,” “American Coot (Red-shielded),” and “American Coot (White-shielded).”

(Note: options may be considered “rare” in certain areas and will be hidden from the default list when you enter sightings.) All previous eBird Caribbean records of Caribbean Coot have now been listed under American Coot (White-shielded). Please use this option whenever you successfully identify a Caribbean-type coot and use the American Coot (Red-shielded) option for American-type coots. For more information click here.

Sometimes, however, you may not be able to identify the coot as either a Caribbean or American-type (for example, when the bird is facing away and the shield is not visible, or the bird’s appearance is in between). When this happens, enter the bird as just an American Coot. Do not use the more specific options, even if your location makes one or the other extremely unlikely (this goes for other subspecies that can be reported in eBird Caribbean too!). Similarly, when conducting Caribbean Waterbird Census (CWC) counts, you should continue to count birds with white and red shields separately because the CWC will continue to monitor the Caribbean Coot’s status in the Caribbean.

Cuban Bullfinch – Multiple Species?

The Cuban Bullfinch (Melopyrrha nigra) is a black and white songbird known to scrub and forest habitats on the islands of Cuba and Grand Cayman. Populations from each island have differentiated enough from one another that they can be identified as distinct subspecies. Specifically, the Cuban subspecies differs from the Grand Cayman subspecies by exhibiting a deeper shade of black and smaller body size, but the more noticeable difference can be found in their songs and calls.3,4

Unfortunately, the isolation of these populations makes it difficult to tell if the bullfinches are species or subspecies, because unlike the Caribbean and American Coots, biologists are unable to study their mating preferences easily. However, after re-assessing the populations’ traits, the AOU has decided that they are still subspecies, at least for now.1

Regardless of how many Cuban Bullfinch species there are, the two populations are clearly unique and of great conservation value. It is very possible that additional research will convince the AOU to change its decision. In the meantime, eBird Caribbean is including both populations separately as “subspecies groups” so keep entering your sightings of Cuban Bullfinches from both the Cayman Islands and Cuba.

1Chesser, R.T., et al., 2016. Fifty-seventh Supplement to the American Ornithologists’ Union Check-list of North American Birds. Auk 133:544-560.

2McNair, D.B., and C. Cramer-Burke. 2006. Breeding ecology of American and Caribbean Coots at Southgate Pond, St. Croix: use of woody vegetation. Wilson Journal of Ornithology 118:208–217.

3AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2016-A.

4Garrido, O.H., et al., 2014. Revision of the endemic West Indian genus Melopyrrha from Cuba and the Cayman Islands. Bull. B.O.C. 134:134-144.

By Justin Proctor and Doug Weidemann

Special thanks to Mario Espinosa, Allan Hopkins, Ray Robles, and Shannon O’Shea for use of the photographs.