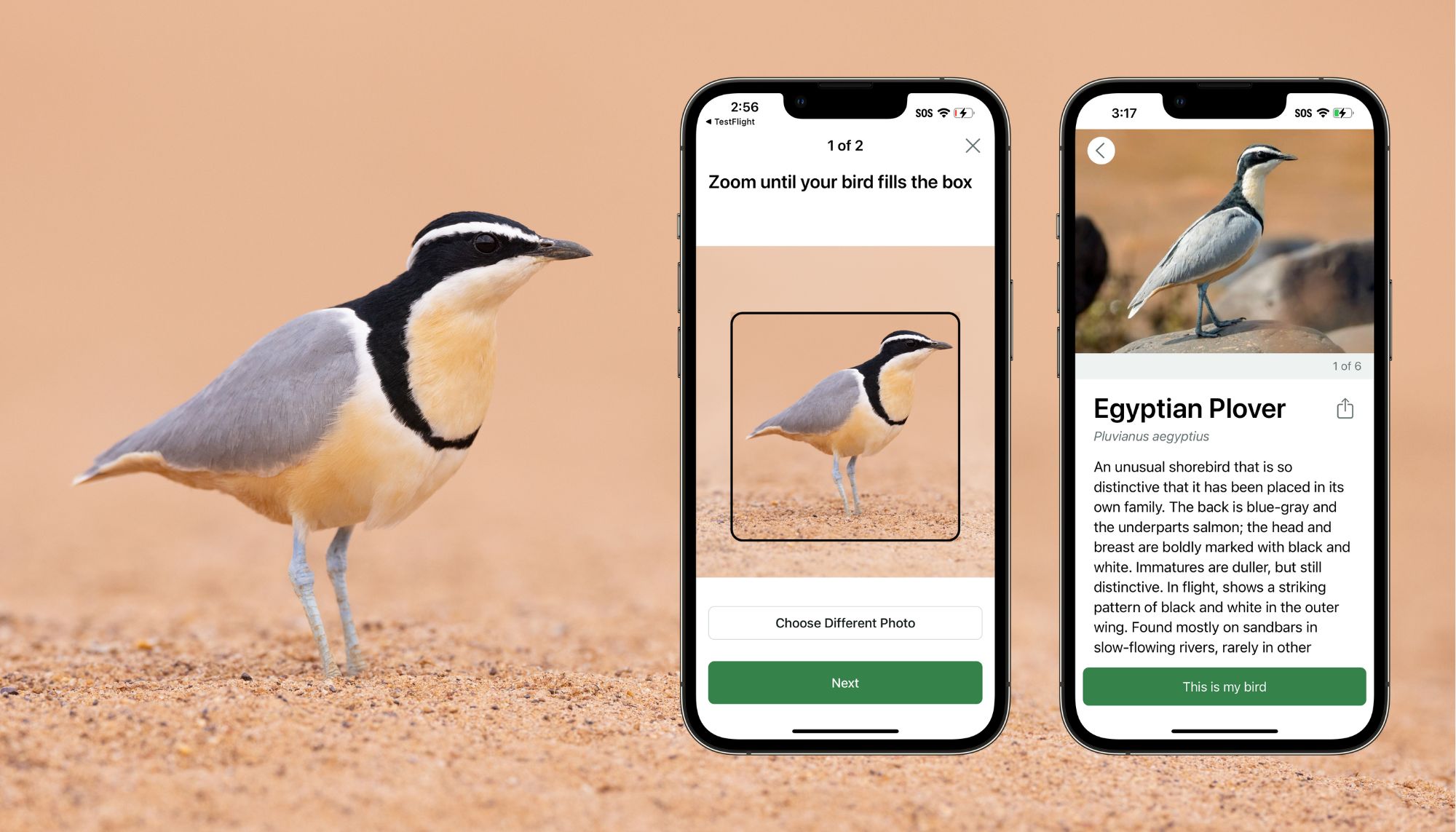

Merlin’s Photo ID feature is newly updated to identify 6900 species, including this Egyptian Plover! Photo © Luke Seitz / Macaulay Library

Merlin just got even better: the app’s Photo ID feature has a new update, boosting its accuracy and helping you identify bird photos with more confidence. Using Photo ID is simple: just take a photo of a bird, tell Merlin when and where you saw the bird, and Merlin will suggest what species it is. This new update happens behind the scenes: Photo ID uses a machine learning model to identify birds in photos, and thanks to advances in machine learning technology and the contributions of eBirders around the world, this model has been updated to now identify 6,900 different species of birds in photos.

This new model is included in Merlin version 3.5, now available as an update from the App Store and Play Store!

How does Photo ID work?

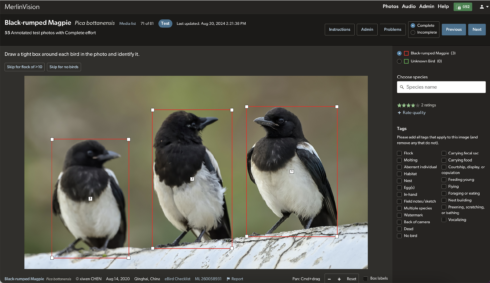

The machine learning model that powers Photo ID – called a convolutional neural network – is trained and evaluated using photos of birds from the Macaulay Library. Each photo selected for training is given to a human expert birder, who annotates the photo by identifying and drawing a box around each bird in the photo. This is a tricky but important part of the process: it’s essential to get the identification correct and the box accurately drawn so that the model is trained using the best possible data. Over 1300 birders from around the world have annotated photos for training this new model.

These Black-rumped Magpies are annotated with red boxes. Every identifiable bird in each photo gets annotated, including blurry-but-identifiable individuals like the bird on the left in this photo. Photo © Xiwen Chen / Macaulay Library

Each annotated photo is presented to the model as a square image of 224×224 pixels, split into red, green, and blue channels. Then the model “does an enormous amount of math on those pixels,” says Sam Heinrich, Machine Learning Engineer in the Macaulay Library. The model performs a series of mathematical operations on the image, looking at different features like the color of the bird, shape of the bird’s body, and where the edges of the bird are in the image. Finally, it looks at eBird species frequency data from the photo location and makes a suggestion as to what species it might be.

“The model learns in a way similar to how you might use flashcards to learn a set of new birds: the model is shown a photo, it makes a prediction, and then is corrected and given the correct answer if it is wrong,” says Heinrich. “This model was trained with a minimum of 50 images for each species, for a total of 6 million different photos. The model is shown each photo 200 times during the training process – so, to put it into human-relatable terms, if you looked at one flashcard per second, it would take you 38 years to go through that many photos.” In comparison, this training process takes just eight days to run on the computers that process it.

Once the training process is complete, the model is shown a new set of different photos to test its accuracy. In general, birds that are more distinct are easier for the model to identify—for example, Northern Cardinals with their crest and bright red color — compared to birds with few distinguishing characteristics, such as Empidonax flycatchers. If the accuracy of the model for a species isn’t meeting high enough standards, engineers can select more photos to train the model to give it more practice, and test it again.

When the engineers are satisfied with the accuracy of the model, it’s packaged into the Merlin Bird ID app as a small download of around 50 MB. The new model that is now in the app (Merlin version 3.5) has an average accuracy of 95%, and a reduction in error rate of approximately ⅔ compared to the previous model.

An update made possible by eBirders like you!

What sets Merlin’s Photo ID model apart from similar features in other apps (like the built-in photo identifier in your iPhone, for example) is the massive dataset of photos that powers Merlin, which were selected from the 65 million photos of birds in Macaulay Library.

Since the most recent Photo ID model was built in 2019, over 45 million more photos have been uploaded to the Macaulay Library by eBirders. “We built this new model because we wanted to better support birders in identifying the birds they photographed, and because with so many new photos, we had an incredible opportunity to push the limits of what this type of model can do,” says Heinrich. These 45 million new photos enabled engineers to better represent each species by including photos that captured spatial and temporal variation in bird plumage.

“Many birds, like Black-crowned Night Herons, look about the same across their range, but many other species look different in different locations,” says Jay McGowan, a Project Leader in the Macaulay Library. “Merlin (after which the app is named) appears heavily and darkly streaked in the Pacific Northwest, but has only faint reddish streaks in Eurasia. Thanks to eBirders uploading their photos from across the world, better representation of species with different plumages were included when training the new Photo ID model, making Merlin better able to identify birds no matter where your photo was taken.”

The massive collection of photos in the Macaulay Library enabled some quirks in the model to be ironed out, too. As one notable example, during the testing phase, engineers noticed the model was unusually good at identifying Nutting’s Flycatcher – a surprise, considering it’s a challenge for humans to identify because of how similar it looks to Ash-throated Flycatcher. This species occasionally shows up as a vagrant in Arizona, where it’s typically heavily photographed. Engineers realized that about a quarter of all Nutting’s Flycatcher photos submitted to eBird were of a handful of individuals from Arizona, which meant that the model was being trained and tested using photos of the same few birds, which artificially increased its accuracy for the species. After adjusting the method used to select photos to now intentionally include fewer photos of vagrants, the model was re-trained and tested using a more representative set of Nutting’s Flycatcher photos. As a result, the new model is more capable of identifying novel individual flycatchers.

What’s coming next for Photo ID?

The Merlin team plans to regularly update the Photo ID model each year as more photos are added to the Macaulay Library archive, both to add new species to the model and also improve the accuracy for species already included.

“Photos of any bird, from anywhere in the world are all helpful! We would love photos of poorly-documented species from remote locations, but your photos of common backyard birds at your feeders can also make a difference,” says Heinrich. To contribute your photos to the Macaulay Library and make them available for use in training future Photo ID models, add them to your eBird checklists. Read more about uploading your photos.

New to eBird? Check out the free, online eBird Essentials course to learn everything you need to know to get started.

Give Photo ID a try!

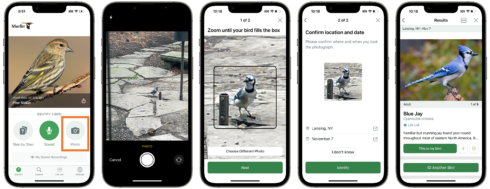

- If you don’t already have the Merlin Bird ID app, download it here!

- Open up Merlin. Tap the “Photo” icon on the home screen.

- Take a photo of a bird, or select a photo you already have from your phone’s gallery.

- Follow Merlin’s prompts: zoom in closer to the bird, and select the location and date the photo is from.

- Tap Identify, and learn what your mystery bird is!