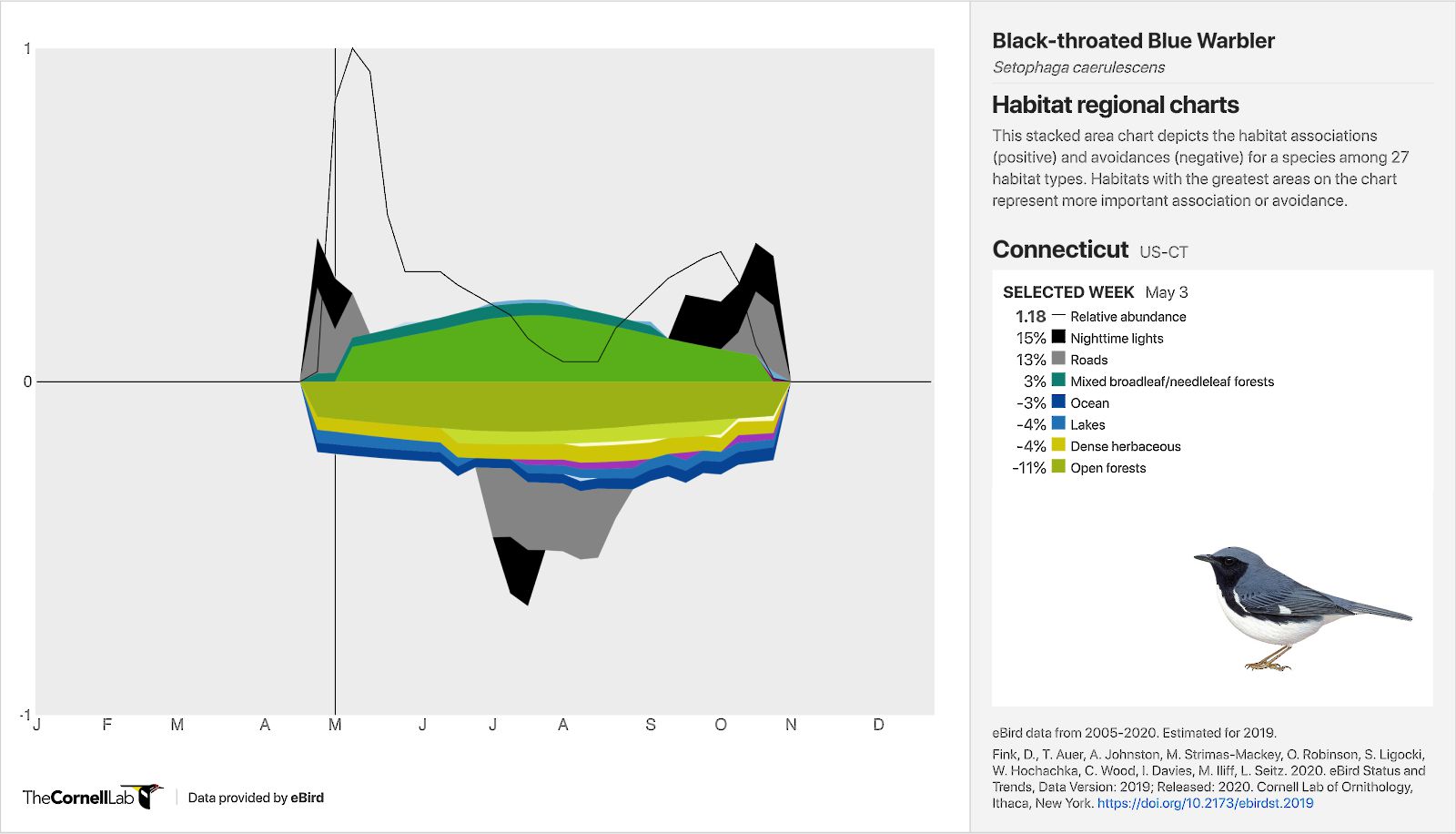

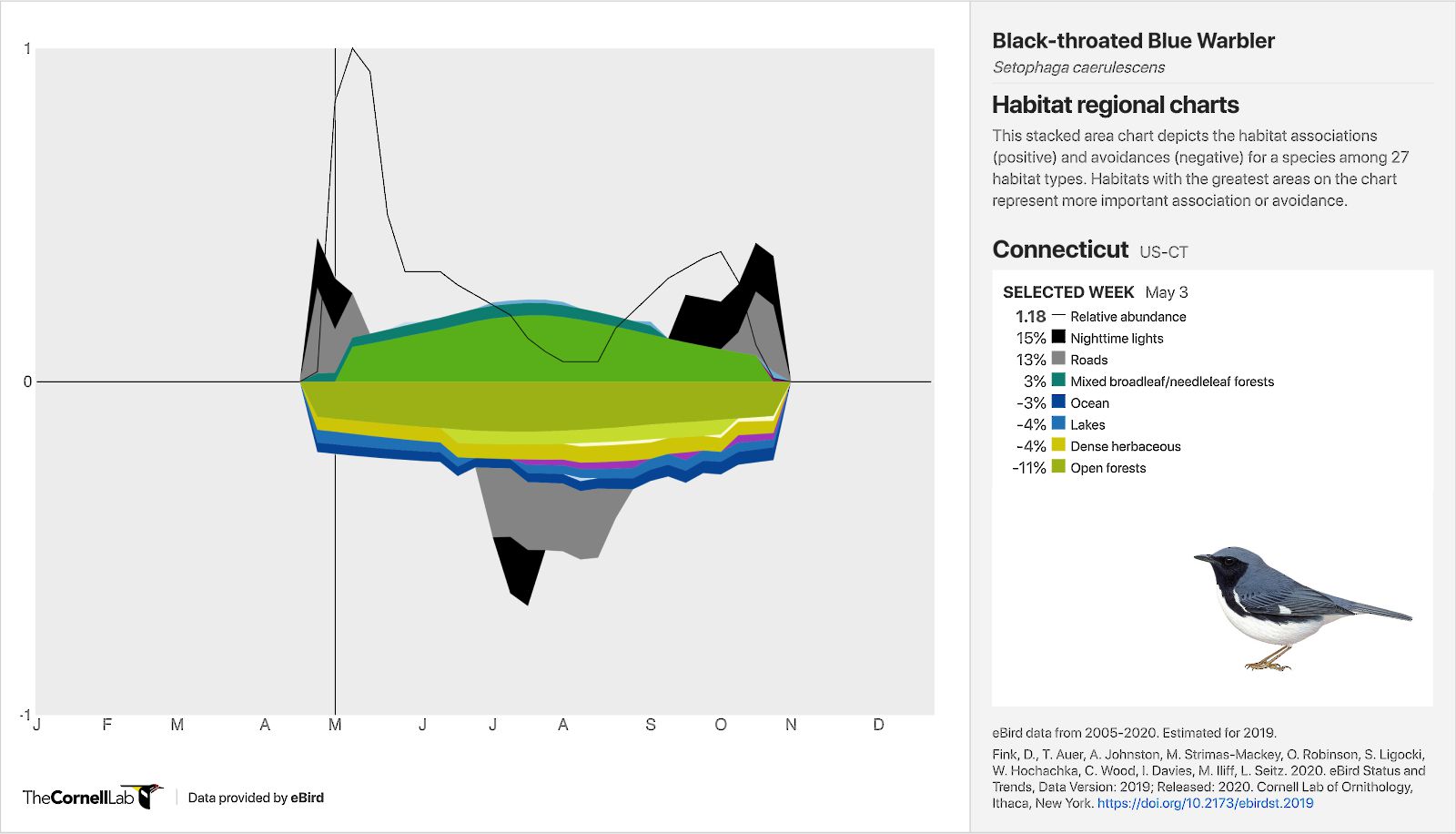

Habitat associations for Black-throated Blue Warblers in Connecticut. During spring and fall migration Black-throated Blue Warblers are positively associated with nighttime lights and roads. Armed with this knowledge researchers and decision makers can begin to address questions related to the impact of nighttime lights on Black-throated Blue Warblers during migration. Black-throated Blue Warbler illustration by David Quinn © Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

When birdwatchers head out to find their favorite species, they don’t go to just any spot, they head to specific habitat types such as grasslands or evergreen forests where the species is frequently found.

Information on where to expect certain species has often been generalized across a species’ entire range or a broad period in time such as the breeding and nonbreeding season—until now. The eBird Status and Trends project team released habitat regional charts for 649 species that show habitat associations for each species for every week of the year in states, provinces, or bird conservation regions where they occur.

The real power of the habitat regional charts comes from the ability to visualize what is behind every eBird Status model depicting the predicted distribution and abundance patterns, says Viviana Ruiz Gutierrez, the assistant director of the Center for Avian Population Studies and Conservation Science Program lead at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. “The Status and Trends models are the most accurate and complex way to examine species distributions that exist in the world today,” says Ruiz Gutierrez. Every map you see depicting changes in abundance across space and time is based on information on how associations with different habitat types change every week; it’s just not possible to see that information without the habitat regional charts.

The new habitat visualizations are interactive allowing you to see how habitat associations change over space and time, providing insights on a scale not possible before.

Static field guides, for example, tell us that Black-throated Blue Warblers breed in large tracts of mature deciduous and mixed evergreen-deciduous woodlands with a thick understory of shrubs including hobblebush, mountain laurel, and rhododendron, but we know little how these associations might change across regions or time.

The habitat regional charts confirm that Black-throated Blue Warblers are associated with deciduous and mixed-broadleaf forests throughout most of their breeding range, but as individuals migrate in the spring and fall, the habitat regional charts indicate that they are frequently associated with areas dominated by roads and nighttime lights along the east coast. Birds passing over Connecticut, for example show a positive association with nighttime lights and roads, which could make them more vulnerable to building collisions. An estimated 365 – 988 million birds die in collisions with buildings annually, including a number of species of high conservation concern. Being able to identify when and where species may be vulnerable to nighttime lights can inform lights out initiatives designed to safeguard migrating birds as they pass.

Habitat associations for Black-throated Blue Warblers in Connecticut. During spring and fall migration Black-throated Blue Warblers are positively associated with nighttime lights and roads. Armed with this knowledge researchers and decision makers can begin to address questions related to the impact of nighttime lights on Black-throated Blue Warblers during migration. Black-throated Blue Warbler illustration by David Quinn © Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

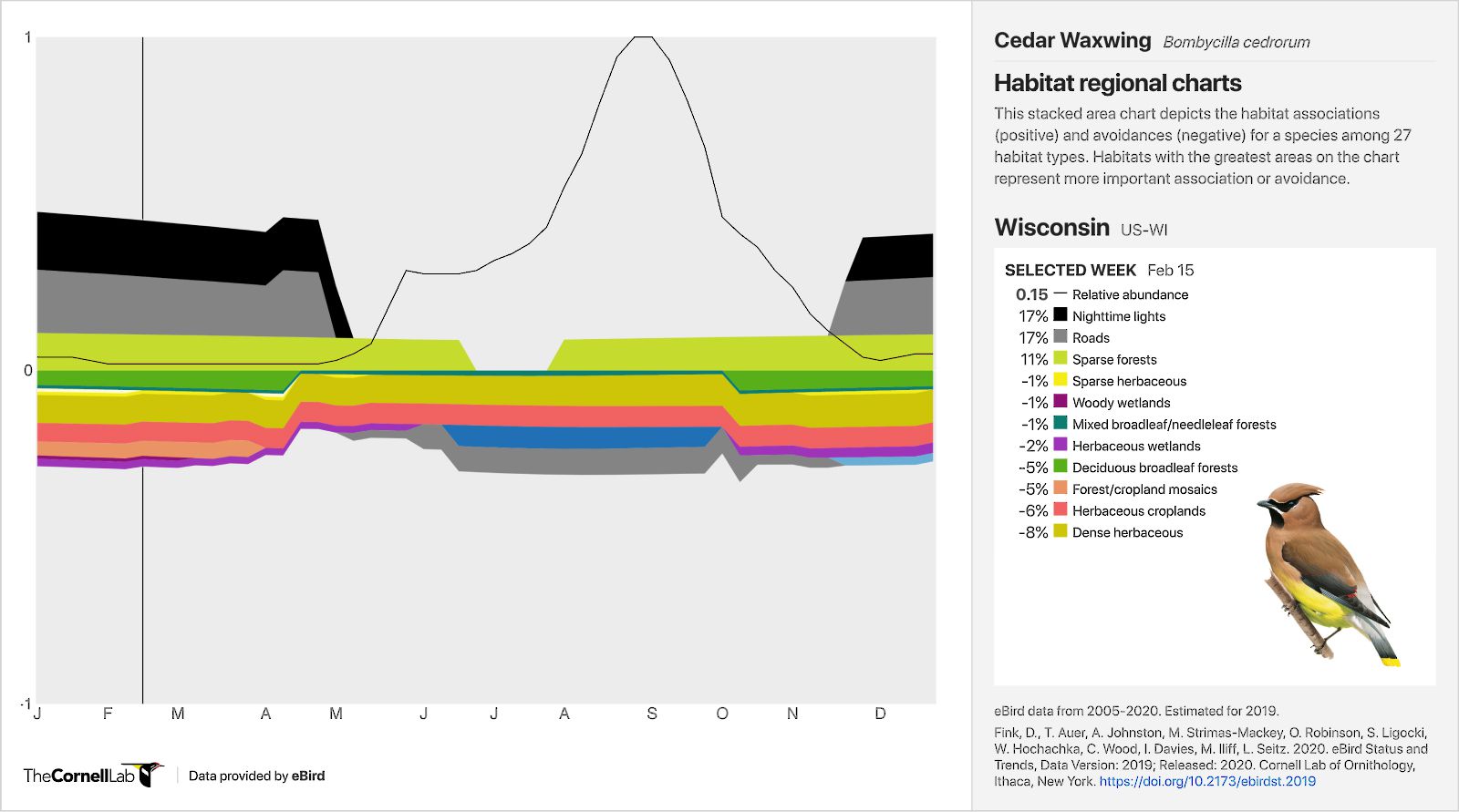

“It’s fun to poke around and see if you can learn something,” says Orin Robinson, a quantitative ecologist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. And there is a lot to learn from the habitat regional charts now available for 649 species. For example, Cedar Waxwings in Wisconsin appear to be associated with nighttime lights and roads during the winter months. What could be driving that association? We know that Cedar Waxwings travel in large groups in search of fruits and many urban areas support large numbers of fruiting trees and shrubs that may be attracting the birds.

Habitat associations for Cedar Waxwings in Wisconsin. During the winter months and early spring, Cedar Waxwings are positively associated with nighttime lights and roads, which is synonymous with urbanized areas that frequently support numerous fruit-bearing trees that the Cedar Waxwings feed on. Cedar Waxwing illustration by Chris Rose © Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

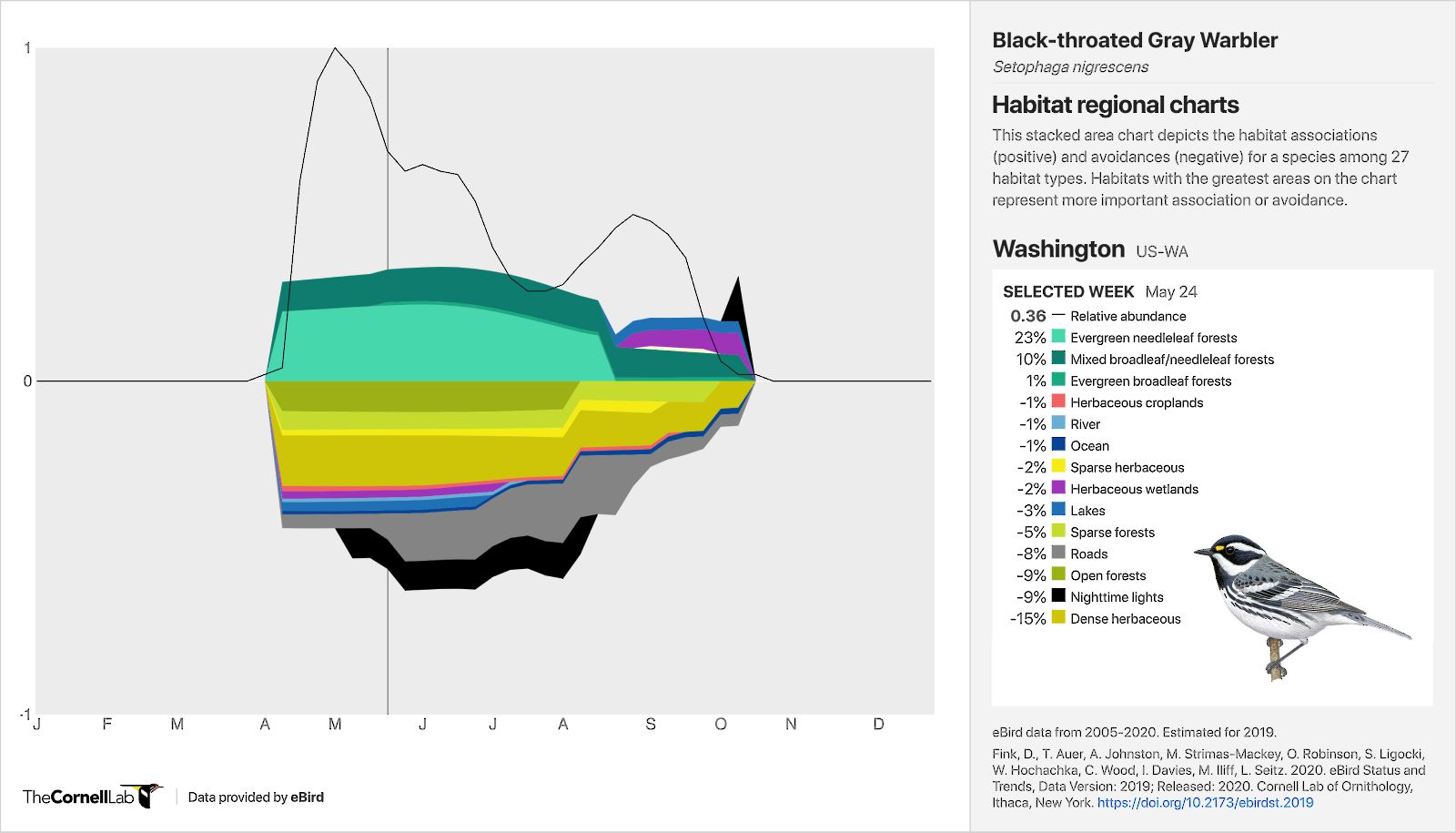

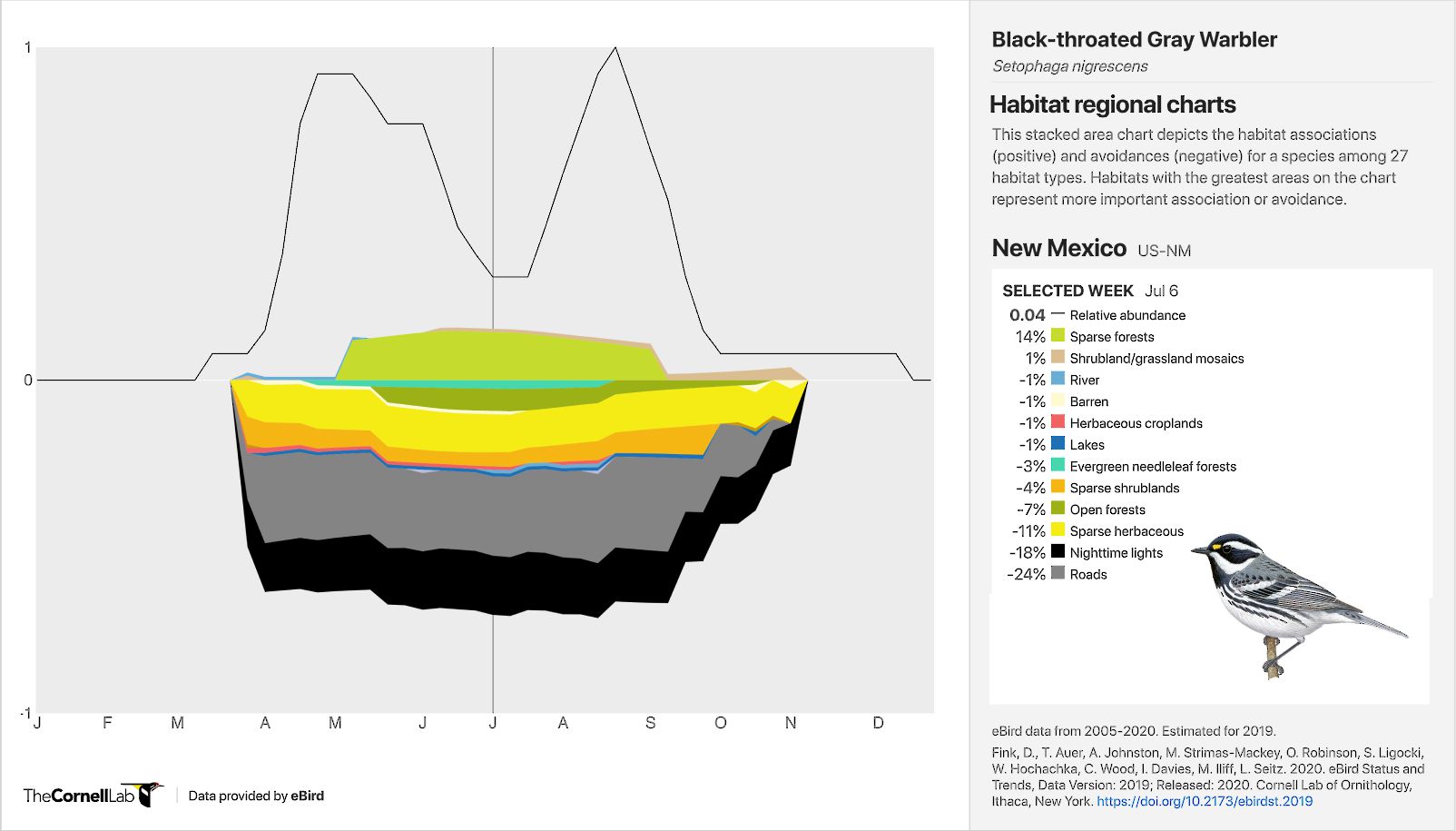

For other species, the habitat regional charts show that some species like the Black-throated Gray Warbler use different types of habitat across their range, from evergreen forests in Washington to sparse forests in the interior West. Powered with this knowledge researchers can dive deeper to investigate the relative importance of each habitat type for the species survival.

Habitat associations for Black-throated Gray Warbler in Washington for every week of the year. During the breeding season Black-throated Gray Warblers show a positive association with evergreen needleleaf forests and to a lesser extent mixed broadleaf and needleleaf forests. Black-throated Gray Warbler illustration by David Quinn © Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Habitat associations for Black-throated Gray Warbler in New Mexico for every week of the year. During the breeding season Black-throated Gray Warblers show a positive association with sparse forests. Black-throated Gray Warbler illustration by David Quinn © Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Sightings submitted by eBirders are the foundation of all of the products from the eBird Status and Trends project, including habitat regional charts. The more sightings that are shared from as many habitat types as possible will help the eBird Status and Trends team better predict abundance patterns and habitat associations. “Try going birding in unexplored places to help us gain a better understanding of where birds are and where birds are not,” says Ruiz Gutierrez.