“Things aren’t what they used to be.” Talk to any birder of two or more decades and that’s a phrase likely to come up regarding area birdlife. Usually the connotation is negative, and rightly so, as bird populations have plummeted by the billions, according to recent studies. There are silver linings, though, birds whose numbers are on the rise. Eagles, falcons, swans, waterfowl and woodpeckers immediately come to mind. Common Ravens? Perhaps not.

For most, the raven is an iconic symbol of northern wilderness, its guttural croaking call a welcome break to the silence of a Northwoods winter. That distribution is a more recent phenomenon, however. Early European settlers found ravens throughout most of the state, and even into Illinois. In the 1850’s, ornithologist Philo Hoy indicated they sometimes outnumbered crows as far south as Racine.

And then came the great cutover of Wisconsin’s forests. Suitable habitat vanished, replaced by agriculture and increasing development. By 1900, raven populations across the Midwest disappeared from the south and declined in the north, a trend that generally held into the mid-20th century and gave rise to the species’ association with “Up North.”

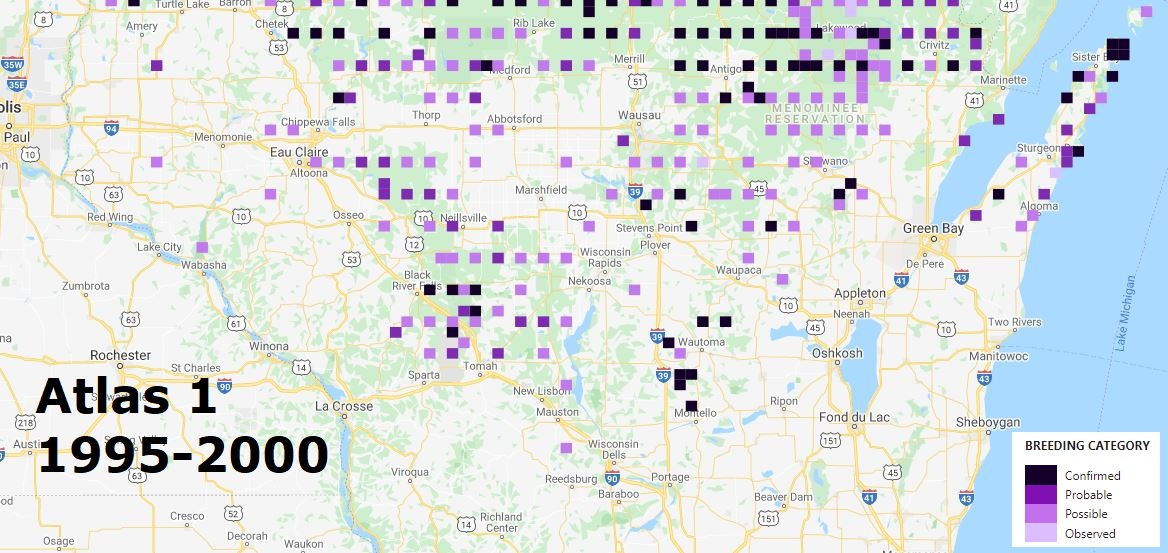

But in the late 1900s that association began to change. Wisconsin’s forests were reborn, and raven populations rebounded. The first Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas project, spearheaded by WSO from 1995 to 2000, documented an expectedly widespread population across the north. Surprising, however, were good numbers of ravens south to Monroe County and scattered individuals nesting in Kewaunee, Waushara and Green Lake counties – hardly “Up North.”

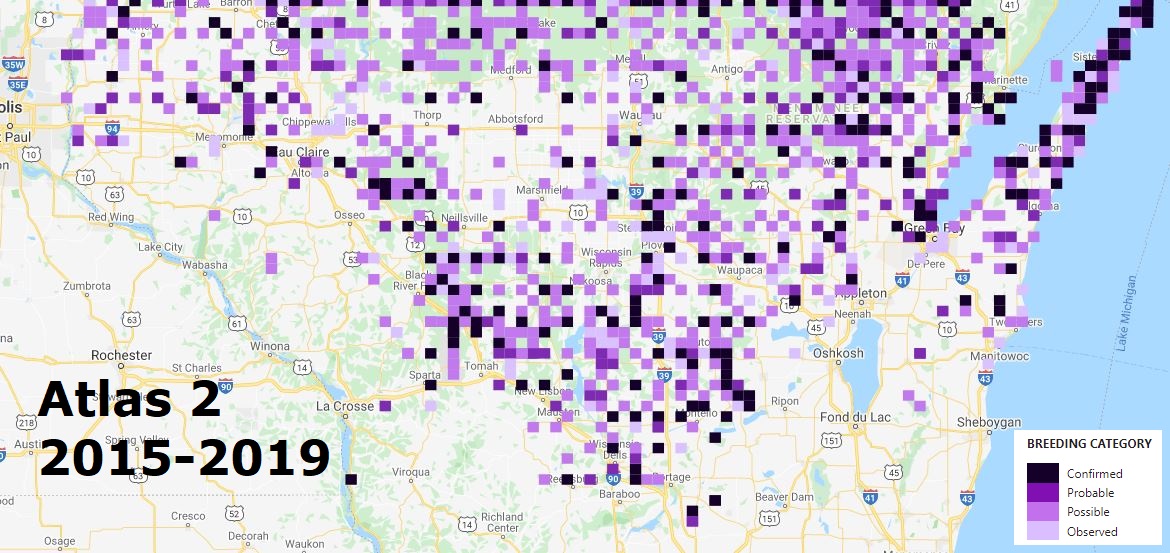

Twenty years later, the second Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas provided an unprecedented opportunity to document range shifts in ravens and 200+ other nesting species. Field work wrapped up in 2019 and project leads continue to process results from this massive citizen science effort that netted 2.8 million bird observations from more than 3,500 observers, aiming toward a book publication in the next few years.

For some species, even the preliminary results were clear. Ravens are back and expanding southward. Nesting was confirmed from St. Croix and Dunn counties in the west to Brown and Manitowoc in the east. Numbers skyrocketed in south-central regions from Juneau and Adams to Sauk and Columbia counties. Outside of nesting season, sightings trickle even farther into Sheboygan, Ozaukee and the Baraboo Hills. Catching a glimpse of this wedge-tailed corvid or hearing its telltale croak overhead can now happen almost anywhere in the state, save for its most southern tier counties.

How did that happen? It’s not entirely about reforestation. Turns out, ravens are very adaptable. While plenty remain wary in wilder portions of the north, others readily tolerate human activity or are even drawn to human-influenced habitats. Road-killed deer, landfills and other anthropogenic sources provide food. Structures such as buildings, bridges, silos, deer stands, and utility poles provide roosting and nesting habitat. Smaller woodlots now suffice, leaving only the most urban and agricultural counties free of ravens in present-day Wisconsin.

It may not be entirely good news. Believe it or not, ravens are considered pests in some parts of their range, especially western North America. They can damage crops, depredate nests and young of other birds, reptiles and mammals, including rare species, and cause economic damage to human structures and objects. None of these issues appear to be significant yet in Wisconsin, but they bear watch as ravens continue their comeback here.

March has arrived. The sun grows stronger and shines longer. Thoughts of spring migration dance in the minds of most birders. But for the raven, nesting season is here. The atlas documented nest building from mid-February to late March statewide, putting them alongside Great Horned Owls, Bald Eagles and Mourning Doves as our earliest breeders. By summer, young ravens will have fledged, ready to disperse into new territory – maybe even in your neck of the woods.