The second field season has officially begun and some birds are breeding even in the snowy depths of winter. January is a great time to document breeding of our largest owl, the Great Horned Owl.

Natural History

Great Horneds are permanent residents, meaning that they stay on their territory year-round. Territories are established and maintained through hooting, with highest activity before egg-laying and second peak in autumn when juveniles disperse. These owls are crepuscular and nocturnal, meaning they are active around dusk and dawn and at night. They eat a wide variety of prey, from small invertebrates and rodents to large birds and hares. Their eyes are large to enable hunting in low light conditions, so large that they can only look straight ahead and must turn their head to see in other directions.

They do not build their own nest. They use old nests, often of Red-tailed Hawk nests, but also nests of other birds and squirrels, and they will nest in cavities, in barns, and on ledges. Where you find a Great Horned, you are not likely to see other owls.

The female incubates the eggs and broods the young, while the male does most of the hunting to feed the female and young. While they are one of our earliest breeders, the altricial young are slow to develop. Incubation takes on average 33 days, the young are not capable of feeding themselves until age 20-27 days and can’t climb out of the nest until they are 40 days old. They are capable of short flights soon thereafter at 45-49 days, and remain loosely associated with adults well into the fall with occasional food brought by the adults in Sep or even Oct. So, for example, if the eggs are laid Mar 1, the young are not flying until mid-late June.

Identification

Great Horneds are distinguished by their large size and large ear tufts. They vary in color across their range with more humid environments being darkest and arid regions having pale, sometimes almost white plumage. Individuals in the Northeast are intermediate in color and tend to have some reddish hues.

Males and females can be distinguished by their calls, with the larger females having a higher pitch than males. You can hear the difference in the following video. The female is perched on a branch and starts calling with the male returning her call from nearby. This calling and responding is called a duet and is part of courtship. The male then joins the female in the video, they copulate, and then they perch together on the branch. If you hear Great Horneds duet, or are extremely lucky and see a pair copulate, record it as C – courtship, display, or copulation. If you just hear one individual it is recorded as S – singing bird or S7 if you hear it twice more than a week apart.

Where and How to Search

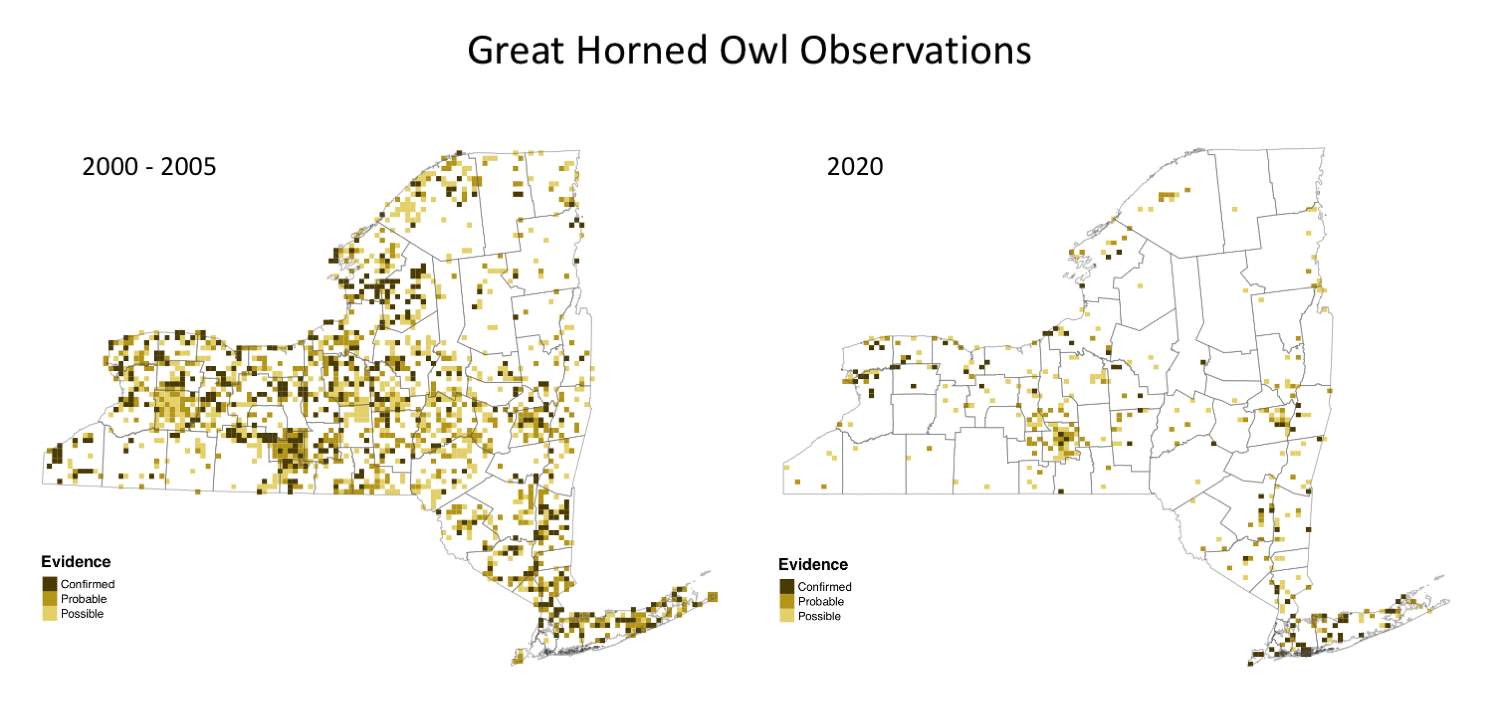

Once you have learned to recognize the calls of Great Horneds, it’s time to head out in search of them. As of this writing, Great Horneds have been confirmed in 27 priority blocks and 72 total blocks. But as you can see in the figure comparing observations from the second atlas to those made in 2020, they should be confirmed in many more blocks.

Great Horned Owl observations from the second Atlas compared to 2020.

Great Horneds are widely distributed across North, Central, and South America in forested areas, usually near open areas for foraging. Within NY, they are distributed across the state but are less frequent in the Adirondacks, Catskills, Tug Hill, and Allegheny Plateau. As you can see in the map from 2o20, most records so far have been near urban centers, indicating that much of the white areas are lacking targeted effort.

Great Horneds are not very responsive to playback, so finding them relies on listening for them in potentially suitable locations at the right time. There is a bit of luck involved, too. I asked two of the top Great Horned Owl contributors who lit up the map around Ithaca, Chris Wood and Ian Davies, for their top tips. Here’s what they do to find Great Horneds.

Search Method

- Identify large patches of mature forest adjacent to open areas.

- Use the satellite view on Google Maps or scout the block in person during the day.

- Identify multiple listening spots per block and determine your driving route. You can also walk, but you will cover less ground.

- Aim for ‘soundsheds’ where you can hear a long distance, such as valley floors or ridgelines.

- Pro tip: Find potential sites for multiple blocks, so that if you find an owl in one block, you can move on to the next in a single outing.

- Choose a calm night or morning. Cloud cover and moon phase don’t seem to matter as much.

- If going out at night, arrive shortly before sunset to find a potential suitable area. Stay out for about an hour after sunset.

- If going out in the morning, arrive an hour to an hour and a half before sunrise.

- Listen for 3-5 min at each stop.

- Stop along the road every half a mile to one mile, depending on the topography and how far sound travels.

- Once you find a Great Horned in one block, head to another block (or head home to get some sleep!).

- Visit the area again to upgrade the code.

- If you only heard one individual calling, try heading back a week later to bump up the code to S7, a Probable code.

- If you heard duetting, visit the forest about a month later and listen for young birds. You might just find the nest!

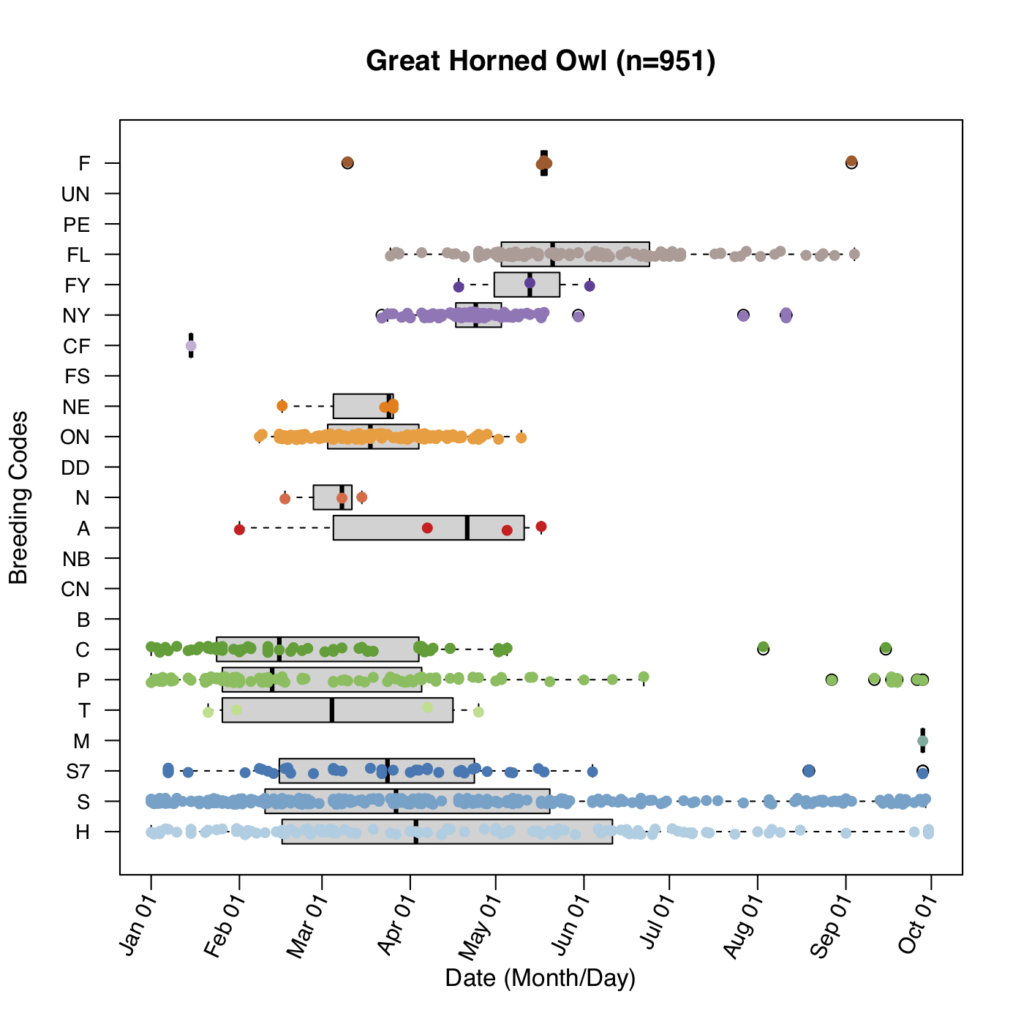

- What time of year should you go out? Great Horneds call year-round, but based on data from 2020 (see the phenology chart below), they are duetting mostly from late January through March.

- If you want to maximize your nocturnal atlasing, head out in March or April when the other owl species are also likely to be active.

Great Horned Owl Calendar

One of the advantages of entering breeding codes on every checklist even if you’ve already documented the behavior, is that we gain a fine-scale look at breeding phenology. If we plot each breeding code by date of observation, we can see when each species is mostly engaged in courtship, nest building, or raising young. The phenology chart for Great Horned Owl based on data from 2020 (below) shows that courtship begins January. Nests were occupied (i.e., incubation) in March and the first half of April, but as early as late-Feb and as late as early-May. Most fledglings are observed in May and June with some seen as early as the end of March.

Breeding phenology plot showing the time of year each breeding behavior was recorded for Great Horned Owl based on 2020 Atlas data (951 observations through September). Standard box plots with median and first and third quartiles plotted. Based on raw, unvetted data.

Calendar

Jan-Mar: Courtship

Mar: Incubating

Apr: Nestlings, brooding, feeding young

May-Jun: Fledglings, feeding young

June-Oct: Juveniles associated with parents

Oct-Jan: Young disperse to find new territory

Behaviors to Look For

Hooting: Monotonous calls that sound like someone blowing across the top of a bottle, described variously as “who-hoo-ho-oo” or “whoo-hoo-o-o, who.” The call is low in pitch and can carry for a long distance. This call is given for courtship, pair-bonding, and territorial advertisement and defense. Report as S – bird singing, or S7 if heard on multiple occasions a week or more apart in the same place.

Duetting: More animated form of hooting that is given simultaneously by a paired male and female. The female starts giving a series of hoots (6-7 notes) and the male responds within a few seconds giving a shorter series of hoots (5 notes), often overlapping with the female. This is part of courtship and should be recorded as C – courtship, display, copulation.

Courtship Display (rare): Males approach females bowing, hooting, and swelling their white “bib” while cautiously approaching the female. They engage in bouts of duetting and synchronous tail-bobbing while showing off their white bibs. Duetting is often interrupted by mutual bill-rubbing or preening to reinforce pair-bonding. The display concludes with copulation. Record this behavior as C – courtship, display, copulation.

Begging: In summer, it’s a good idea to learn the juvenile begging call, which if often confused with calls of the extremely rare Barn Owl. This is unique to dependent juveniles so as long as you aren’t close to block lines, hearing this is recorded as FL – recently fledged young.

Branching: As the owlets begin to leave the nest, they will spend most of their time sitting on the branch where the nest is located or on a nearby branch in a behavior called branching. Record branching birds as FL – recently fledged young.

Bill-clapping, hissing, screams, wing-flapping: These behaviors are used when the owls feel threatened. If you observe any of these behaviors, you are too close to the nest site or young and should retreat. These behaviors are also used to defend against intruding owls and predators. Use the A – agitated behavior code to record this behavior. Enter the code after you have retreated to a safe distance!

Spread wings: Threatened birds will crouch down and fan their wings out to make a shield so that they look bigger and more intimidating to the intruder. This is an even more extreme form of defense, often accompanied by bill-clapping, hissing, and screams. If you observe this behavior, you are too close! Back away immediately. Record as A – agitated behavior.