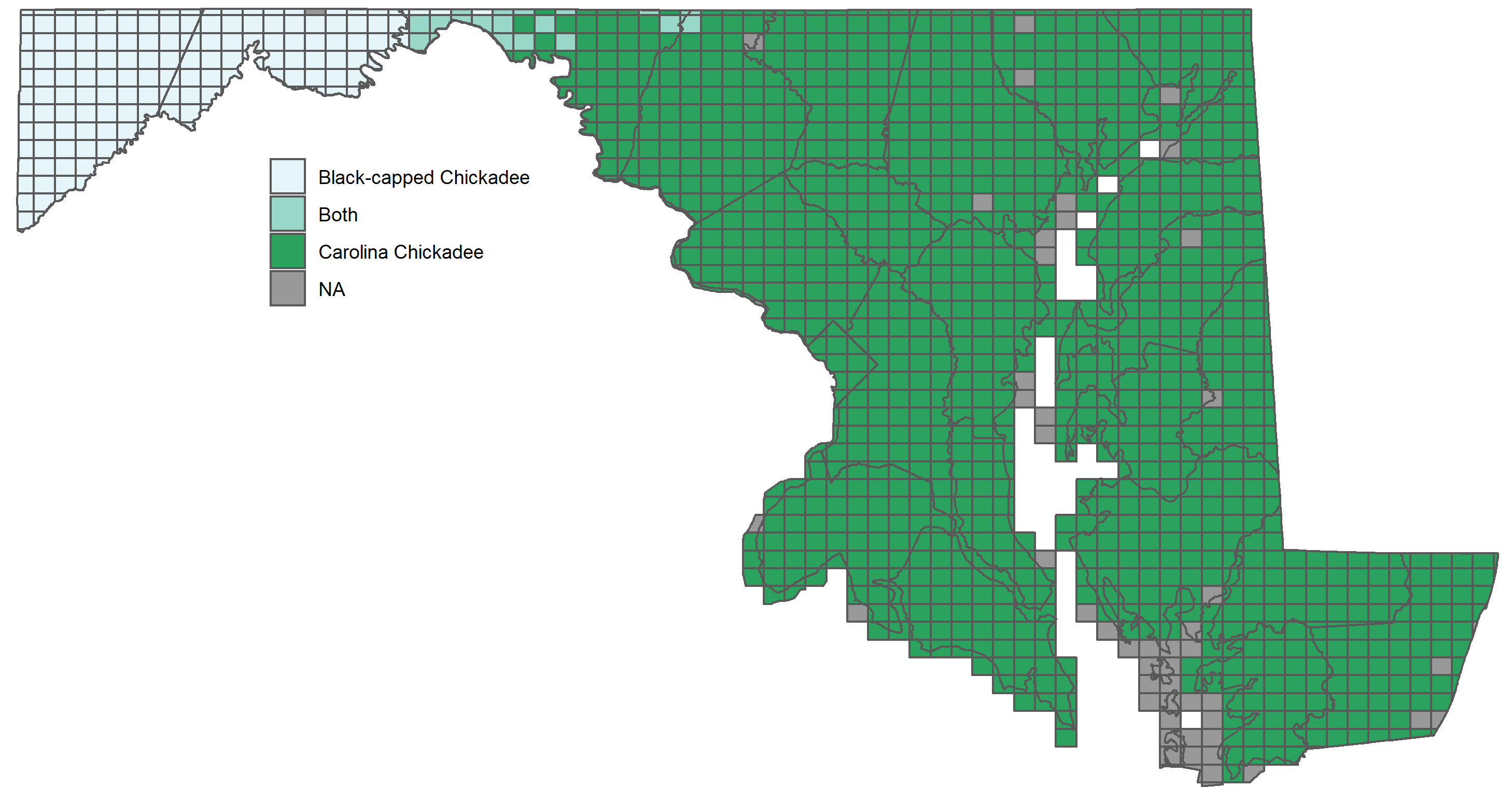

Chickadees are abundant and familiar birds in Maryland and DC, found almost anywhere there is forest. Both Black-capped and Carolina Chickadees occur in Maryland, but despite the state’s relatively small geographic area, each species’ distribution is sharply demarcated and there is little overlap between the two species. Carolina Chickadee is essentially the only chickadee in Maryland east of the Allegany and Washington county border. West of that line, the Carolina’s range transitions to Black-capped. In the Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in Pennsylvania, Bob Curry says that, “Black-capped Chickadee densities generally increase with elevation, in part because the species is absent from the low-elevation regions occupied by Carolina Chickadees, but also because forest cover tends to increase with elevation.” In Maryland and DC’s first atlas, Black-capped Chickadees were reported on the Catoctin and South Mountain ridges, but Carolina Chickadees have been steadily invading the Black-capped Chickadee’s range. By the second atlas, Black-capped was found in ten fewer blocks and it is now unclear if Black-capped Chickadee persists east of Allegany County.

Chickadee breeding distribution map from the Maryland & DC Breeding Bird Atlas 2. Dark green fill indicates a Carolina Chickadee breeding observation in that block, medium green fill indicates both chickadees, light green fill represents Black-capped Chickadee, and dark gray indicates no chickadees.

Separating Carolina and Black-capped Chickadees from each other is not simple, but fortunately the correct identification can be safely assumed by location in almost every case. In the narrow contact zone, not only should each chickadee be carefully examined, but the potential for hybrids—which may be quite common in the contact zone—must be considered. One of the best resources for separating these two species is on David Sibley’s website (however, note that this article is focused on fall and winter birds, and not the darker, more worn appearance of summer birds). Many chickadees in the contact zone will not be identifiable to species. Hybrids complicate matters not just because their appearance is less predictable, but also because they may sing Carolina or Black-capped songs.

Any chickadee in the contact zone that is not confidently identifiable to species, including those only heard singing, should be recorded as Carolina/Black-capped Chickadee. As Matthew Shumar says in The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in Ohio, “Increased overlap between Black-capped and Carolina Chickadees…highlights the need for observers to identify chickadees carefully within overlap zones.”

Chickadees form socially monogamous pairs while still part of their winter flock. Males begin singing a simple, though somewhat variable, whistled song in late winter; Black-capped Chickadees sing a two-note fee-bee song. About three weeks before laying their eggs, the pair begin excavating cavities with entrances of 1.6–1.8 inches, often near a forest clearing, removing pieces of soft, rotted wood with their bills. Black-capped Chickadees prefer a lining of wood shavings in the cavity (important if you want to put up a birdbox for them), but Carolinas don’t seem to care. On average, the nest site is only nine feet high and 4–5 inches in diameter. Once the selected cavity’s interior has been excavated to about 2.6 inches wide and 7.0 inches deep, the female begins bringing nest materials. She layers the bottom with moss, then lines the cup with plant fiber, hair, or fur. The final product is distinct and recognizable as a chickadee nest.

The female lays half a dozen white eggs with reddish-brown blotches, then begins incubation. The male will bring her food throughout incubation, but even so she takes a five-minute break every fifteen minutes or so. The eggs hatch after thirteen days and the female continues brooding while the male brings each voracious youngster food once an hour. By seventeen days, just before the chicks leave the nest, both parents are working together to bring each nestling food once every ten minutes (although larger broods do have a lower per-nestling feeding rate). When bringing a meal, the parent normally perches within fifteen feet of the nest, then flies to the cavity and exchanges the food for a fecal sac.

The chicks fledge at 16–19 days, but don’t always leave the nest all at once. They remain with their parents for another 2–3 weeks before gaining independence and dispersing. To identify fledglings, look for short wing and tail feathers, a fleshy, yellow gape, or begging behavior.

Chickadees will use cavities as roost sites throughout the year, so encounters with chickadees entering or exiting a cavity at dawn or dusk outside the breeding season should not receive a breeding code (the safe dates can be used as a guide for each chickadee’s breeding season). Likewise, chickadees at a feeder may interact aggressively or carry food away during the non-breeding season; neither of these behaviors should receive a breeding code. Code A (agitated) should not be used outside of the breeding season. By the time spring rolls around, winter flocks have broken up and chickadees together are generally pairs (code P). Both fledglings and adult females will quiver their wings to beg for food and/or to solicit a copulation (in the case of females). Females should receive code C (copulation or courtship display). If you see adults feeding their fledglings you can use code FY (feeding young); otherwise use code FL (recently fledged young). Pairs investigating potential cavity sites in March (or April for Black-capped) can be coded with code N (visiting probable nest site) and excavation should receive code NB (nest building).

References

Ellison, W.G. 2010. 2nd Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Maryland and the District of Columbia. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore. 494 p.

Foote, J.R., D.J. Mennill, L.M. Ratcliffe, and S.M. Smith. 2020. Carolina Chickadee (Poecile carolinensis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A.F. Poole and F.B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.carchi.01

Mostrom, A.M., R.L. Curry, and B. Lohr. 2020. Black-capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A.F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.bkcchi.01

Rodewald, P.G., M.B. Shumar, A.T. Boone, D.L. Slager, and J. McCormac. 2016. The Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in Ohio. The Pennsylvania State University Press. University Park, PA. 578 p.

Robbins, C.S. and E.A.T. Blom. 1996. Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Maryland and the District of Columbia. University of Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh. 479 p.

Wilson, A.M., D.W. Brauning, and R.S. Mulvihill. 2012. Second Atlas of Breeding Birds in Pennsylvania. The Pennsylvania State University Press. University Park, PA. 586 p.