Rock Pigeons were introduced to North America over 400 years ago and have become a well-established part of our avifauna. Despite that, they were ignored by birders and ornithologists until just a few decades ago. In 1958, Stewart and Robbins stated that “no truly wild population is recognized in this area” and that “the great majority of observations refer to privately owned or escaped birds”. Rock Pigeons were recorded on the Annapolis-Gibson Island Christmas Bird Count in 1941 and 1943, but otherwise the species was not counted on CBCs until 1973. As a result, little is known about the historical distribution and population status of the Rock Pigeon.

This unfortunate fact is referenced in Rock Pigeon species accounts in many atlas books. In our first atlas publication, Rick Blom said that, “considering this bird’s close association with people, it is remarkable that almost nothing is known about its breeding biology in Maryland. As far as ornithologists and birdwatchers are concerned, the Rock Dove barely exists, despite its large numbers.”

Of course, whether it is naturalized or not, ignoring a substantial part of the ecosystem is problematic when trying to understand changes and impacts.

Top Tips

- Check bridges and barns for nests

- Use code N (visiting probable nest site) where appropriate

- Remember that pigeons can fly a long distance from their nest site to food sources

- Don’t overlook pigeons just because they are naturalized.

Habitat

In North America, Rock Pigeons are closely associated with human infrastructure. Although they infrequently nest on cliff faces like their wild Eurasian counterparts, they are nearly always found nesting in or on buildings or under bridges. They can be found in high density in urban areas, while in rural areas they are associated with farms—especially farms with livestock—and small towns. Highway overpasses and bridges also provide nest sites. These highways can extend their range through areas they wouldn’t otherwise be in, like I-68 through Allegany County. Pigeons require a flat surface for their nest site, usually with some cover.

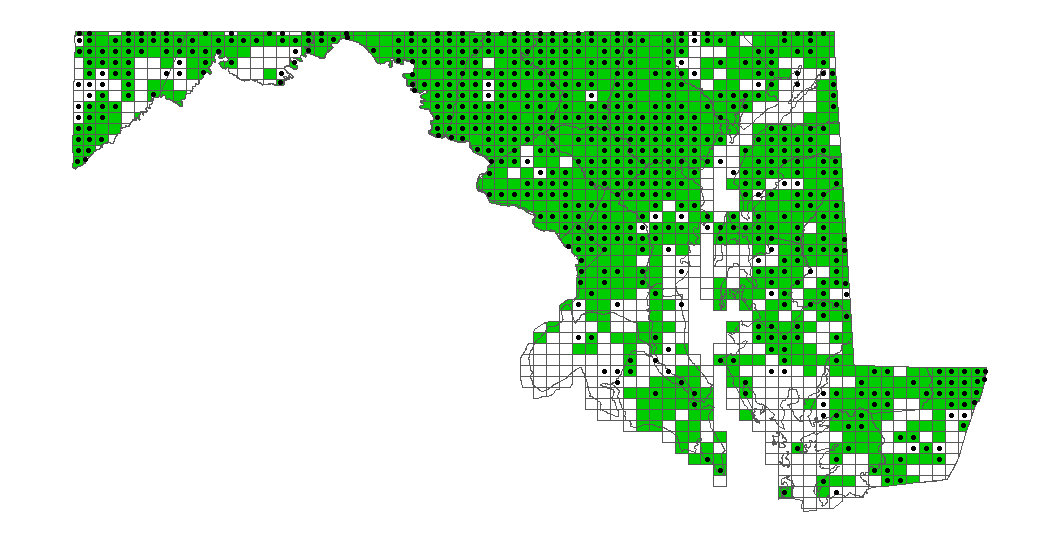

Rock Pigeon breeding distribution map from the Maryland & DC Breeding Bird Atlas 2 (2002–2006) and Atlas 3 (2020–2024). Green fill indicates a BBA2 Rock Pigeon breeding observation in that block (72% of blocks), while black dots represent BBA3 breeding observations (48% of blocks).

Rock Pigeon breeding distribution map from the Maryland & DC Breeding Bird Atlas 2 (2002–2006) and Atlas 3 (2020–2024). Green fill indicates a BBA2 Rock Pigeon breeding observation in that block (72% of blocks), while black dots represent BBA3 breeding observations (48% of blocks).

Identification

Rock Pigeons are distinctive and familiar birds, despite their plumage variability. Although they are often found in large flocks, they do not require large groups. They primarily eat seeds and grains, and can travel substantial distances to reach foraging areas.

Behavior and Phenology

Nearly all our breeding birds feed their chicks animal protein, which generally limits their reproduction to the warmer months. Rock Pigeons produce a ‘crop milk’ that is high in fat and protein. A diet of seeds is sufficient to create this secretion, which frees pigeons from the typical seasonal constraints imposed on other breeding birds. They will nest all year long, although they appear to nest less frequently in late fall (perhaps due to the timing of their molt). Rock Pigeons only lay two eggs at a time, but regularly lay over six clutches each year.

Pigeons use a courtship display of coos and bows to form and maintain their pair bonds, as well as preening each other and courtship feeding via regurgitation. Both males and females coo, but males coo louder and more frequently. Unmated males select a nest site and advertise their availability by cooing from the nest site. Once an interested female pairs with him, the pair will use his nest site until he dies and aggressively defend the site from other pigeons. If he dies, she will seek a new male elsewhere.

The nest building process can seem more ritualistic than practical. While the female is cooing on the nest site, the male leaves to find a single stick, piece of grass, or other suitable material. According to the literature, he may fly more than 130 ft to find this stick. Considering pigeons may fly several miles to a good foraging site, a bystander could interpret 130 ft as a bit half-hearted. This nest construction procedure is repeated 1–5 times per minute for 5–20 minutes each morning for 3–4 days—an effort that, again, could be interpreted as less than lusty.

Once the construction phase is complete, the female lays two white eggs. The monogamous pair share incubation duties; the male incubates from late morning to late afternoon, and the female the remainder. The eggs hatch about 18 days later, and the parents remove the shells—although they will ignore the feces produced by their chicks. In fact, these feces eventually form a sort of broad nest cup, and some older nests can weigh in excess of five pounds. Once hatched, the chicks are brooded continuously. They’ll eat crop milk from their parents for the first week; after that the parents begin to include seeds. Initially covered in stringy yellowish down, the chicks are well-feathered by two weeks of age and feather growth is 90% complete by day 27. Chicks, or ‘squab’, that hatched in the summer will leave the nest after 25–32 days. Those that hatched in the winter may stay in the nest for as long as 45 days. After fledging, the young will return to roost at the nest site for 2–4 days before striking out on their own. They reach sexual maturity within 5–9 months—females a little earlier than males—but pigeon populations are limited by nest site availability, so many young pigeons don’t breed immediately.

The average interval between clutches is about 46 days, but it can be as short as 29 days. Females may even lay their next clutch before their current young have departed.

Breeding Codes

Rock Pigeons can be coded with code H (habitat) anytime they are in an area that may have a suitable nesting location, but note that pigeons may travel well outside a block to forage. In this way, pigeons have some similarities to vultures. Codes S (singing) and S7 (singing for 7+ days) can be used for their cooing, although codes P (pair), C (courtship display), and N (visiting probable nest site) may all be better choices depending on the context. Code T (territorial) can be used when witnessing agonistic interactions, but since these take place around the nest site code N may still be the better choice. Pigeons have no distraction display (code DD) and they do not carry food (code CF) or fecal sacs (code FS). Finding likely nest sites for pigeons is not difficult but actually seeing the nest can be, so code N can get a lot of use for pigeons.

We still have two years of data collection, but Rock Pigeons have only been recorded breeding in 48% of blocks so far. This is a substantial difference from BBA2’s 72% and BBA1’s 79% of blocks. The Confirmation rate is also much lower; In BBA1 44% of blocks had Confirmations. In BBA2, that dropped to 31%, and now we have only Confirmed Rock Pigeons in 20% of blocks.

References

Ellison, W.G. 2010. 2nd Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Maryland and the District of Columbia. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore. 494 p.

Lowther, P.E. and R.F. Johnston. 2020. Rock Pigeon (Columba livia), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S.M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.rocpig.01

Robbins, C.S. 1996. Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Maryland and the District of Columbia. University of Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh. 479 p.

Stewart, R.E. and C.S. Robbins. 1958. Birds of Maryland and the District of Columbia. United States Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.