While birding it can be be easy to lose yourself in the experience. This is usually a good thing, unless that is, you can’t find your way back! This is almost what happened in this eBird story shared with us by our partners at aVerAves.

eBird, an unusual way to avoid getting lost in the forest while looking for quetzals, by Alan Monroy-Ojeda

The early morning was humid at the camp, with the night’s rain still dripping from the leaves and branches of the trees. The call of a Spotted Nightingale-Thrush had woke me up and put me in a good mood even before opening my eyes. Three meters from my hammock, my friend and biologist Ana Ibarra rested in hers. Stepping out, I felt the wet soil and leaves under my bare feet. Looking up I was delighted by the sight of the dense cloud forest surrounding us with its deep greens and mystic appearance.

The early morning was humid at the camp, with the night’s rain still dripping from the leaves and branches of the trees. The call of a Spotted Nightingale-Thrush had woke me up and put me in a good mood even before opening my eyes. Three meters from my hammock, my friend and biologist Ana Ibarra rested in hers. Stepping out, I felt the wet soil and leaves under my bare feet. Looking up I was delighted by the sight of the dense cloud forest surrounding us with its deep greens and mystic appearance.

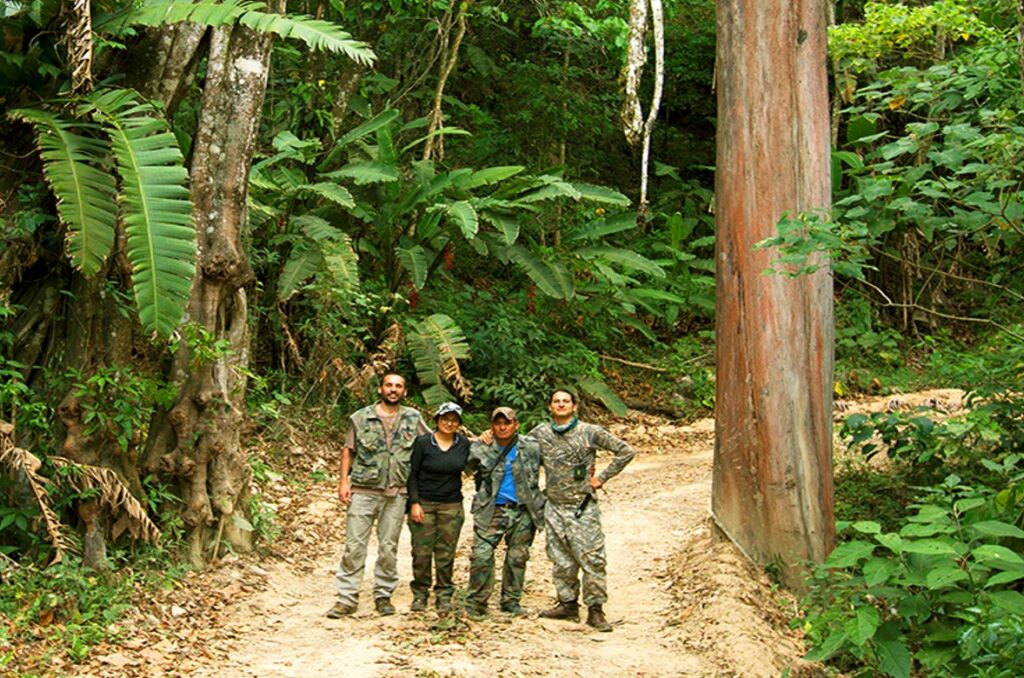

Alba and I geared up in silence: boots, jackets, our inseparable binoculars. With a brief and friendly “Hi”, we each started an eBird list and went into the forest interior in opposite directions. The previous afternoon our four member team had hiked up the mountain: photographer Santiago Gibert and park guard Javier Vázquez completed our conservation team. Our mission was to search for and document the elusive Resplendent Quetzal in the mountains north of the El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve in Chiapas, Mexico.

Santiago and Javier spent the night on a plateau higher up on the mountain, and as our protocol dictated, each of us would search and document Quetzals and possible nest sites on different parts of the mountain. Thus, before dawn, we were already navigating the slopes and ravines that are home to this mystical bird. The terrain was tough: the only available trails were those made by the tapirs as they passed through this pristine area, and sun’s rays rarely made their way through the canopy to touch the forest floor.

As I walked silently through the forest my ears were totally focused on any sound that might indicate the presence of Quetzals. A long whistle alerted me to the presence of a Chestnut-sided Shrike-Vireo foraging for insects in the bromeliads while another loud call brought my attention back to the floor just in time to see a small group of Singing Quail running to hide.

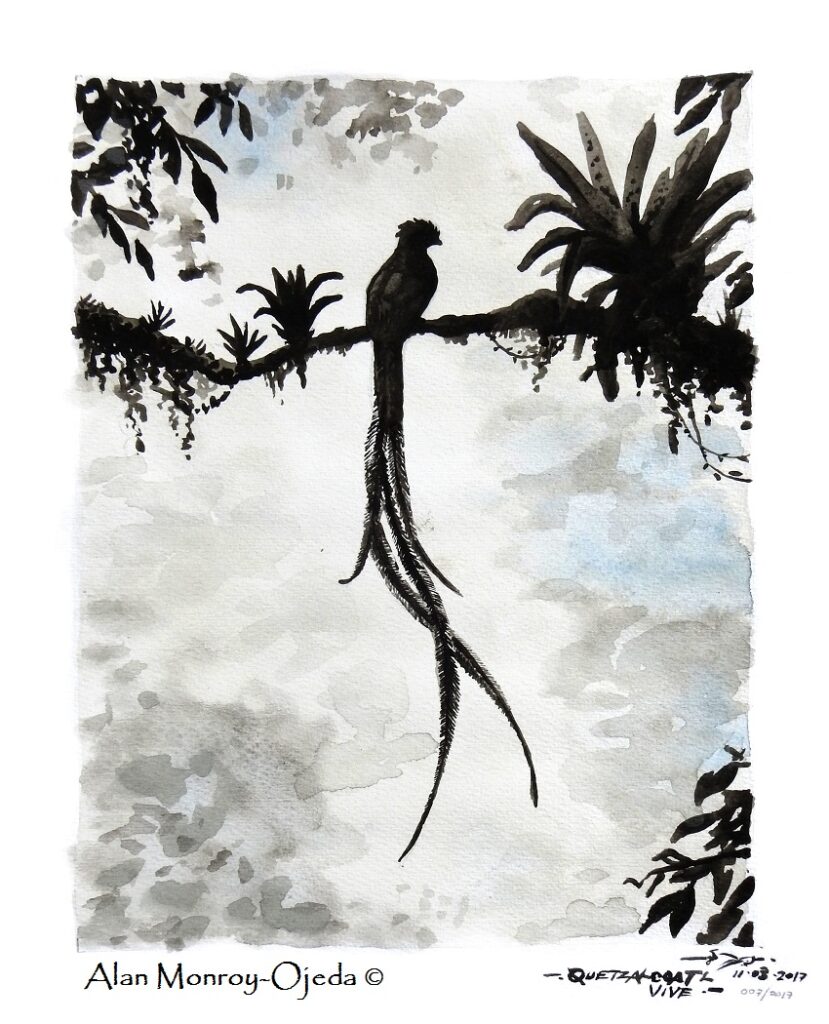

I kept walking until my steps took me to a small plateau with 40 meter high trees that resembled a cathedral. In that very moment in the highest part of the canopy a repetitive call caught my attention, it was exactly what I was listening for: the call of the Quetzal. I quietly approached, and even though the sound got louder, I still could not see the source of the call because it was hidden in the dense green foliage. I sat down and in a moment that seemed eternal, an adult male Quetzal leapt into the air making a call that sounded more like laughter. Its long feathers spread and danced like snakes in the air. At that moment, the image of Quetzalcoatl1 and “the feathered serpent” came to life before my eyes.

I quietly followed two males as they vocalized and flew between the treetops. It was only when they flew across a steep ravine that I stopped. At that moment I was so fascinated that I was overwhelmed by happiness. The euphoria started to fade away the moment I realized I had no idea of where I was in the forest. Looking around, I could recognize neither “the woods”, nor the “trail” that put me there. By putting all of my attention on the flying Quetzals, I had lost complete track of my steps.

I knew that if I went “downhill” I would eventually find the river and, by following it, I might find one of the coffee farms we work with on conservation projects. However, I also knew that any wrong direction could lead me down a steep and dangerous ravine, or into impenetrable vegetation where Fer-de-lance (a highly venomous snake) is common.

By using all my “nature navigator” skills, I kept calm and tried to think about all of the landscape elements that might give me a hint as to which direction would take me to the trail back to camp. Unfortunately, the sun was not making its way through the mist, so it was not helpful for orientation. Following javelina trails was helpful for a while, but I would just get confused at their crossroads. While thinking about all of this, I suddenly stared at my hand, holding the cellphone I just retrieved from my backpack to add two Golden-browed Warblers  to my eBird list. In that instant it hit me, Eureka!! Finishing my active list on the eBird App gave me access to the button that showed me my entire birding track, I had no phone signal but luckily I had loaded the satellite map that showed me the GPS track over the vegetation. I took a screenshot, immediately started a new eBird list, and started walking again. After about 300 meters, went back to my list and finished it as well. As before, the App showed me the new GPS track and I took another screenshot. By comparing both images I was able to see the exact point where I had diverted from my path, the point where I was standing, and most importantly, the direction to better known ground.

to my eBird list. In that instant it hit me, Eureka!! Finishing my active list on the eBird App gave me access to the button that showed me my entire birding track, I had no phone signal but luckily I had loaded the satellite map that showed me the GPS track over the vegetation. I took a screenshot, immediately started a new eBird list, and started walking again. After about 300 meters, went back to my list and finished it as well. As before, the App showed me the new GPS track and I took another screenshot. By comparing both images I was able to see the exact point where I had diverted from my path, the point where I was standing, and most importantly, the direction to better known ground.

After repeating the same procedure a couple of times, I finally made it back to the trail and found some boot tracks. Looking at the surroundings I was able to identify some familiar trees and landscapes that after some kilometers took me back to camp, where Alba was waiting for me.

So, after a journey where the mountain gifted me with an encounter with the Quetzals –the forest spirits- a mobile App and a little common sense brought me back to camp, where once the four of us were reunited, we shared our adventures in the cloud forest.

- Toltec-Aztec deity whose name in náhuatl language means feathered snake, from quetzal: feather, and cóatl: snake. God of light, life, fertility and knowledge. Usually represented by feathers from the Resplendent Quetzal.