Year 2 has fledged!

Field work for the second year of the Atlas is pretty much over and we’re already starting to look at the data that piled in this year. Below we highlight some achievements to date and look forward to opportunities for next year.

If you haven’t done so yet, please submit your data and make sure it’s in good shape (read how).

What we’ve achieved

As of today, there are 2395 atlasers who have submitted a combined 258,596 checklists! That’s more than a quarter million checklists in less than two years. More than a million observations have a breeding code, and if you add up all the time people have spent atlasing, that’s more than 500 years.

There aren’t enough superlatives to express how impressive these numbers are.

We couldn’t do this without your support. It has been amazing to see how engaged the atlasing community is. Before we started this project, we set internal goals for the number of atlasers we expected to participate each year. We expected 750 in the first year, but we more than doubled that with 1510 atlasers by Sept 2020. For following years, we expected another 250 atlasers per year, but we more than tripled that this year with more than 856 new atlasers.

And the stories atlasers tell when we ask them about how and why they got started atlasing are truly inspiring. (Read atlaser profiles.)

We confirmed breeding for 3 new species this year, bringing the total up to 218 species. The three species added this year were Northern Shoveler, Common Eider, and Northern Saw-whet Owl.

This summer we held the first annual Big Atlas Weekend to help raise awareness for breeding birds. We joined forces with the Maine, Maryland-DC, and North Carolina Bird Atlases to host this fun, new event. We kicked off the event with a talk on Female Bird ID, with fun facts about how to tell females apart from males using a variety of cues, from plumage, to behavior, to small black specks in the eye! We held a training workshop for new atlasers, and then the weekend of June 25-27 we asked everyone to go out atlasing and focus on nocturnal birds, grassland birds, blocks with low effort, and confirming species. We tallied it all up and presented the results and challenge winners the following week. Over 1000 people participated in the weekend event (435 from New York alone) and spent a total of 3276 hours making 6169 confirmations! Read the full results.

All in all, it was a great year. We are all tired from the pandemic but birds continue to bring us joy and it helps many of us to have an added sense of purpose behind our birding. We hope to keep the momentum going for the next three years!

Looking forward

Over the next three years we will be focusing on filling in gaps—covering rural areas, nocturnal species, rare species, and getting more confirmations—so we can complete all priority blocks.

Atlasing further afield

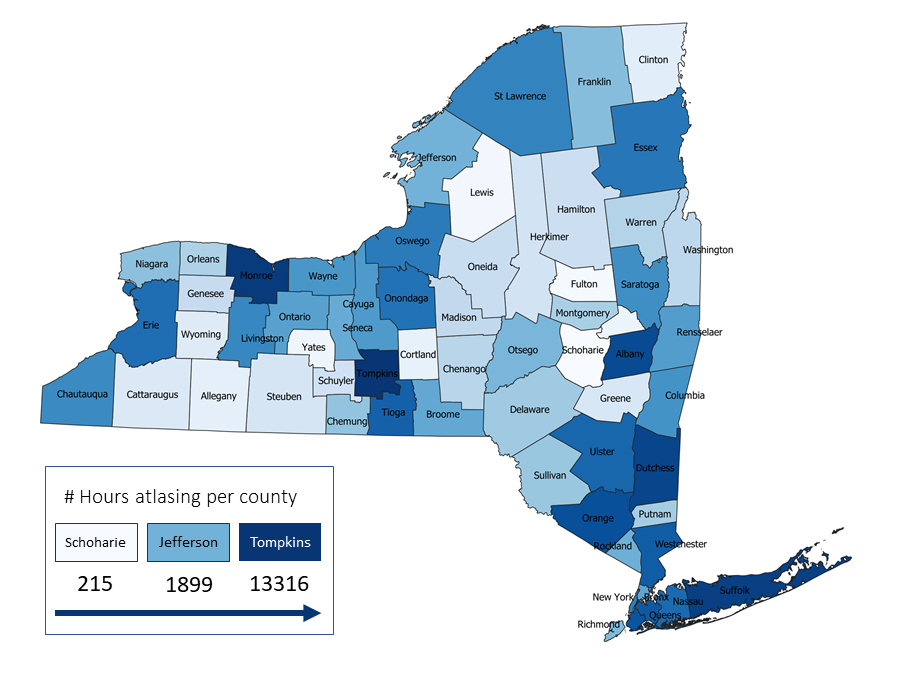

The map below shows how much time has been spent atlasing in each county. Some counties have seen relatively little effort (e.g., Schoharie, Fulton, Yates, Lewis), while others have been extensively visited (e.g., Tompkins, Monroe, Suffolk, Albany). Part of this is due to where we are familiar birding and part of it has to do with the pandemic, but we hope that in 2022 we can encourage people to atlas further afield, filling in gaps in rural and remote areas.

The number of hours spent atlasing in each county as of the end of July 2021. Lighter colors indicate fewer hours, darker colors more hours. The county with the least hours is Schoharie and the county with the most is Tompkins.

Nocturnal atlasing

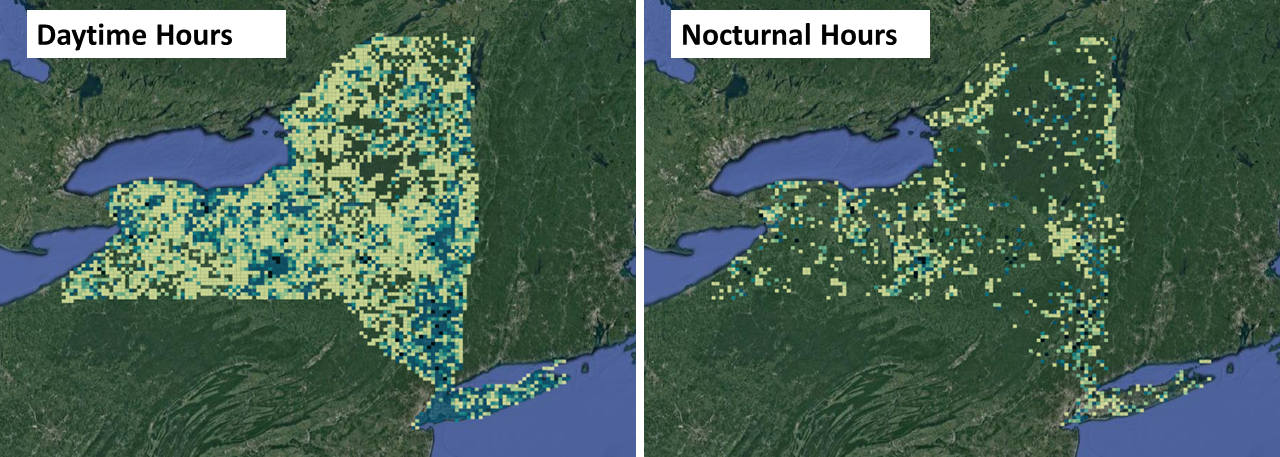

Most of the time spent atlasing so far (see figures), whether it was during the day or at night, is focused around more urban areas. And while we expect the vast majority of data to come in during the daytime, we need to spend some time at night because there are a good number of nocturnal and crepuscular species that are really only detectable at night, like owls, rails, and nightjars (see the nocturnal species guide). All blocks need at least 2 nocturnal hours to be considered complete.

A comparison of daytime and nighttime hours showing that most effort is skewed towards urban centers and there is still very little nocturnal coverage overall.

Finding rare birds

Another interesting aspect to look at is how well we are doing at capturing rare breeding species [see the full list of rare breeders]. Some historically rare species are expanding their range, such as Trumpeter Swan (confirmed in 23 blocks), Sandhill Crane (29), Merlin (64), and Bald Eagle (360; see the growth in Bald Eagle after year 1). We are still lacking data for other species. For example, despite our focus on grassland birds this year (see the guide to grassland birds), we still have no or few records for obligate grassland birds, such as Upland Sandpiper (2 blocks) and Henslow’s Sparrow (0), though Sedge Wren (10) had a decent year.

We also expanded the nightjar surveys this year to try to capture all three species—Common Nighthawk, Eastern Whip-poor-will, and Chuck-will’s-widow—across the state.While it is difficult to confirm breeding for nightjars—they are most active at night and prefer dense vegetation in out-of-the-way places—we still have very few confirmed breeding locations for them compared to the second Atlas, with confirmed breeding in only 2, 1, and 0 blocks, respectively.

There are still a few species that we strongly suspect are breeding in the state, but for which we don’t have documentation through the Atlas. If you are a chaser, these are the species you might want to target next year. Real misses are some of the ducks: Northern Pintail, Lesser Scaup, and Ruddy Duck; some of the boreal specialists: Philadelphia Vireo, Tennessee Warbler, and Bay-breasted Warbler; some southern species: Gull-billed Tern, Kentucky Warbler, and Summer Tanager; and the ever-elusive Long-eared Owl.

For the stats on all species, see the continually updated statewide summary page.

Getting more confirmations

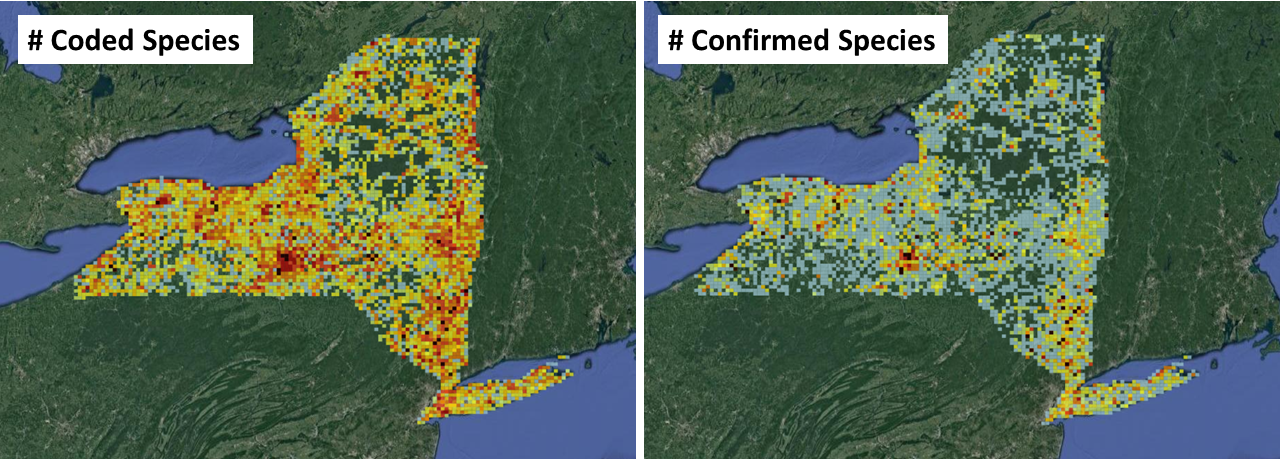

While more than a million observations have been submitted with a breeding code, only a small percentage of those codes are in the confirmed category. Compare the maps for the total number of species coded in a block compared to the number of species confirmed in a block (see figures). The color scales are different but you can see that most blocks (all the light blue blocks) have less than 10 species confirmed. In fact, only about 30% of all observations submitted to the Atlas have a breeding code, and only 13% of observations that have a code are in the confirmed category. This hints that some observations are lacking codes when they could be coded (likely with the lower codes like H and S), and that we still have a lot of opportunity to help you learn how to confirm breeding more often (hopefully through in-person outreach in 2022!).

A comparison of the number of species with a breeding code in each block (on a scale of 0-100+) compared to the number of confirmed species in a block (on a scale of 0-60+). Note the focus around urban areas and that most blocks have fewer than 10 confirmed species (noted in light blue).

Finishing blocks

The goal of the Atlas is to complete all priority blocks. There is a set of guidelines that we use to assess whether the coverage in a block is adequate (note the term “complete” is a bit of a misnomer, because a block could never really be complete)—what we call the block completion guidelines. Very few blocks have met all these thresholds, particularly the minimal nocturnal coverage of two hours. However, there are a lot of blocks that are really close and we hope people will focus on finishing those early next year.

Final notes

We need your continued support to help finish the Atlas over the next three years. Here are some ways you can help:

- Continue atlasing! Learn what to do in the off season.

- Consider volunteering in a larger capacity. Consider entering data for someone else, organizing an Atlas walk in your area, being a local spokesperson for the Atlas, or becoming a full-fledged Regional Coordinator (apply here).

- Post your questions to the Facebook Discussion Group or ask an Atlas team member.

- Part of a bird club? Learn how your bird club can support the Atlas.

- Sponsor a species. Get your name in the final Atlas product when you sponsor a species for five years.