Razorbill is an alcid of cold North Atlantic waters and rarely strays south of Cape Hatteras, NC, in the United States. The state of Florida previously had 14 records of this species, so last week when multiple Razorbills started appearing in Florida—including flocks of more than 20 birds—it was clear that something very odd was going on. This invasion has continued to strengthen, with some Razorbills turning up as far south as Miami and the Florida Keys, and some remarkable birds apparently rounding the tip of the peninsula and appearing along the Gulf coast! Some other species more typical of the Northeast and mid-Atlantic are also turning up, including Black Scoters, Dovekie, and even Thick-billed Murre, and this invasion of the Southeast is helping to lend perspective to odd patterns in coastal southern New England. Although alcids are sometimes driven by storms to unusual places, large-scale invasions like this are more typically driven by food shortages in their normal range. Below we discuss this invasion in more depth and provide ideas to help explain this unprecedented event. Additional discussion is also available at Birdcast.

2012 Razorbill invasion

Fig. 1. Unheard of prior to this year, this evocative image says it all: Razorbills with palm trees of Miami Beach in the background. Photo 15 Dec 2012 by Trey Mitchell.

In a normal year, no alcids will be found in Florida, but this year has been exceptional. In just the past two weeks there have been dozens of Razorbill reports from the entire of the Atlantic Coast of Florida. One band recovery so far is from a bird banded on Matinicus Rock, Maine (

fide Tony Diamond). In addition, an increasing number are being found on the Gulf Coast, where there is just one prior record (from Denedin Causeway,

13 Apr 2005).

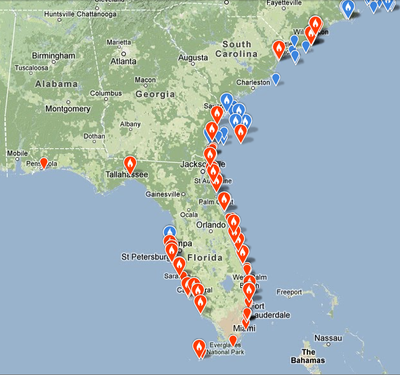

A picture is worth a thousand words: below is the eBird map for Florida:

Fig. 2. Razorbill point map for the southeastern United States for all years (see

map on eBird). On this map, the blue stickpins refer to records from past years while the red ones illustrate the impressive scope of this year’s invasion. Of particular note are the first records from Florida’s Gulf coast and the first records from the Florida Keys. Note the Pensacola record just a few miles from the Alabama border!

As much as it pains us, keep in mind that not everyone uses eBird and that dozens of Razorbill records from this year likely are missing from this map. An additional Florida Razorbill map is being maintained

here and may help fill in some of the missing records.

This invasion would be noteworthy enough if these were all single birds, but some huge flocks of Razorbills are occurring, with the highest counts so far being seen off Miami.

Stunning photos by Trey Mitchell with Miami palm trees and beachfront hotels in the background (Fig. 1) put this event in perspective. Here are just a few of the more notable counts from eBird so far:

We feel we have to remind folks again that the entire state had just 14 prior records and Miami-Dade County had just one prior record! This year is amazing!

Amazingly, of those reported to eBird so far with counts of five or more, one is from Duval County (Jacksonville area) and one from Sarasota (Gulf coast!), but all others are from the extreme south in Broward, Palm Beach., and Miami-Dade Counties. Are these flocks of Razorbills flying direct over the ocean from Cape Hatteras and thus largely skipping northern Florida, perhaps as they confront the choice whether to fly south into the Caribbean or westward into the Gulf? Hypotheses welcome!

One additional thing to pay attention to is the age of Razorbills that are seen well. Immature Razorbills, such as our cover shot and the one below in Figure 5 lack any vertical white stripes on the bill. Winter adults, on the other hand, have obvious vertical white lines in the middle of the bill. The bill is also thicker on adults; compare a photo of a

winter adult. If you are able to identify your Razorbills to age class, please report that in your eBird checklists–it seems that the majority of birds in this invasion are first-winter birds.

For some eye candy, here are some of the checklists with embedded photos (thanks as always, to eBirders that

embed their photos, as it helps the review process and makes the checklists visually striking):

17 Dec 2012, Mayport Naval Station–Jetties Beach, Duval Co.

17 Dec 2012, Stan Blum Memorial Boat Launch, St. Lucie Co.

18 Dec 2012, Sand Key/Chearwater Beach Channel, Pinellas Co.

Additional illustrated checklists can be found by exploring eBird.

North of Florida the pattern does not seem as apparent, but all of the red points on the eBird map above from waters south of Cape Hatteras are probably connected to this movement. At the Avalon Seawatch in Cape May Co., NJ, Tom Reed reports significant late-season flights of scoters (Black Scoters dominating)

12 Dec 2012 and Razorbills nearly daily, with an all-time high of 42 on

19 Dec 2012, both very unusual at this long-running seawatch. Surely these flights are connected to the Florida pattern.

Could the Bahamas or other Caribbean islands see some alcids this year? Could this be the year that Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, or Texas or even Mexico gets its first record? The more turbid waters of the Mississippi Delta may not be as good for Razorbills, so movements of Razorbills west of western Florida may not materialize in comparable numbers. However, we fully expect and predict that intrepid eBirders wil find at least a few Razorbills farther west in the Gulf of Mexico. Observers in the Gulf Coast and northern Caribbean should do some concerted seawatches, should check coastal jetties for birds feeding along the rocks, might watch for Razorbills to join feeding flocks of gulls or terns, and scour beaches for sickened or dead Razorbills that may have washed ashore.

Other species to watch for

If this is indeed a food web collapse, or temporary paucity of food in the western Atlantic, then other species should be expected to be turning up in this movement as well.

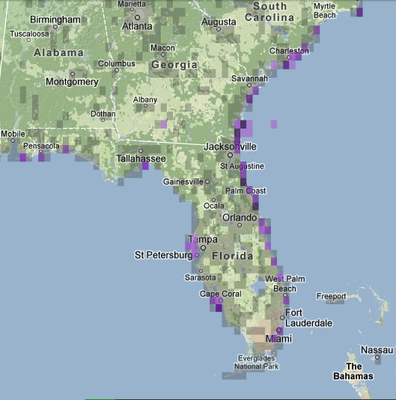

Black Scoter is another species that is clearly showing a major invasion this year. Typically rare in Florida, this year they seem to be showing up everywhere on both coasts.

Fig. 3. Black Scoter map from eBird for

December 2012 (captured 19 Dec 2012). Even with the month barely half-gone, it is evident that there are many more Black Scoter reports than in any previous year.

Fig. 4. Black Scoter map from eBird for

December 2011. This map is typical for the “normal” occurrence of Black Scoter and shows that the species is usually largely absent from Florida’s Atlantic coast (see also

Dec 2010,

Dec 2009, and

Dec 2008, which are similarly restricted).

Of course, other alcids should be watched for as well. A photographed

Thick-billed Murre in northernmost Florida

14 Dec 2012 provides one of very few prior Florida records (which include sight records from Lake Worth, 20 Nov 1976 and one off Canaveral 20 Dec 1977) and a photo record of one in Hobe Sound. Martin Co., 6 Dec 1992 (Stevenson and Anserson 1992. Birdlife of Florida). See the live

eBird map, in case it fills in further. Given the magnitude of the Razorbill invasion, we expect a few more Thick-billed Murres to turn up in Florida and states north, probably around jetties, piers, in sheltered harbors, or washed up on the beach. A few in coastal Massachusetts recently (for example,

Boston’s second eBird record and first since 1972) could conceivably be connected as well, as murres may be spreading in all directions to avoid unproductive waters offshore (see below).

Dovekie and

Atlantic Puffin, both species of deeper offshore waters, may be less a part of this flight than other species, but are to be watched for. It may simply be that they are staying farther offshore and that their southward flight is not being detected. On-shore records of Dovekie from

Cape May, NJ, and

southern North Carolina indicate that this species is showing some signs of appearance near-shore south of its normal range. When wind-tossed or food-stressed, Dovekies often do appear in harbors, inlets, and along jetties. Atlantic Puffins very rarely show that behavior, and while they occasionally turn up moribund on beaches, almost all puffins at the southern margins of their range tend to be found offshore. Still, these species, Common Murre, and Black Guillemot (the latter never recorded south of South Carolina), should all be kept in mind. Watch for more records of

Dovekies on the eBird map.

A number of other species from mid-Atlantic and New England waters of the Continental Shelf seem to be turning up in above-average numbers south of the normal range. Although Razorbill and Black Scoter are the most apparent representatives of this event now, we should watch reports of other species to better understand the scale of this event. Red-breasted Merganser, Northern Gannet, and Common Loon are all regular in Florida in winter, and eBird reviewer Robin Diaz reports typical numbers in Miami-Dade County this year (although ratios of adult gannets seem elevated relative to immatures). Numbers of these species should be watched for unusual patterns this winter. The below species are much rarer in the state, and all show some signs of movement south with this invasion:

- White-winged Scoter ( eBird map) – Rare to very rare in Florida, but several reports this year may be connected to the larger movement.

- Surf Scoter ( eBird map) – Rare to very rare in Florida, but several reports this year may be connected to the larger movement.

- At least one Common Eider has turned up in Florida; will others appear as the winter wears on?

- Red-throated Loon ( eBird map) – Typically very rare in Florida

Please report to eBird

Large scale movements like this are better tracked in eBird than anywhere else. Although Florida records keepers are sure to do a thorough job documenting this unprecedented invasion into their state, getting the most complete picture possible will depend on capturing accurate locations and dates for as many Razorbill records as possible. Of no less importance is the continent-scale view that eBird provides. Are records of Razorbills, Thick-billed Murres, Dovekies, Red-throated Loon, and Black-legged Kittiwakes close to shore in the Northeast connected to this movement? Can records from the Carolinas and Georgia be connected to the movement into Florida? Are Razorbill counts off the Northeast coast depressed this year or are numbers high here as well suggesting even larger scale movements? (Here are the

line graphs for Massachusetts for the last five years, which show 2012 to be a year largely devoid of really high counts, so far. Note however that the Outer Cape Cod CBC had over 2000 Razorbills on 16 Dec 2012)

Fig. 5. The water color is enough to indicate that this Razorbill is out of place. This water looks like it is warm enough to swim in, not the cold dark or greenish waters of New England! Photo 15 Dec 2012 off Miami Beach by Trey Mitchell.

Only with thorough reporting to eBird, from the Gulf Coast to Newfoundland, can birders hope to get a good grasp on the big picture of this Razorbill phenomenon. Please send eBird your reports and please do your best to document these, since Razorbill continues to be a bird that requires documentation for the Florida Ornithological State Records Committee.

What is going on?

When we first heard news of the invasion, we surmised that this must be related to ocean conditions in the core range of Razorbill.

The core range of Razorbill in winter is offshore and nearshore waters, mostly over the Continental Shelf, from the Atlantic Provinces in Canada south to the Mid-Atlantic states and Cape Hatteras, NC. In exceptional years, large numbers invade south to Cape Hatteras and a few straggle further south, although the causes for these invasions are rarely clear. Changes in the distribution of wintering alcids are often food-driven, and if waters in their core range are unusually unproductive, many birds may wander (south, in this case) in search of suitable conditions and richer food sources. Razorbills eat mostly capelin (a small fish in the smelt family) in the northern breeding range and herring and sandlance in southern breeding range) in summer (fide Tony Diamond). The diet is probably similar in winter, with capelin and krill (small crustaceans) especially important during the winter (see e.g., Gaston and Woo 2008, Lilliendahl 2009). Availability of these food sources probably is driving the current invasion, so information on the abundance of these species relative to past years would be an important piece of the puzzle.

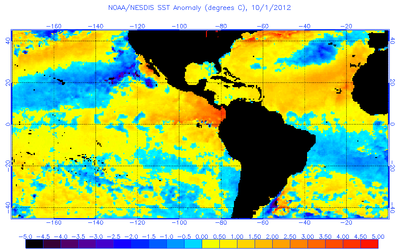

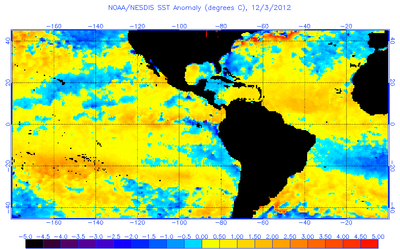

In many ways the alcid invasion probably parallels the finch invasion underway across the northern reaches of the United States now, with both species of crossbills, redpolls, and Pine Grobeaks dispersing farther and farther south in search of suitable food. To support our hypothesis that the southward alcid invasion is food driven, we looked at ocean temperatures in the western North Atlantic, including temperatures at or near the Continental Shelf where Razorbills and many other species winter. This fall, particularly in November, has seen an unusually large Sea Surface Temperature (SSTs) anomaly off the Northeast Coast. Along the Continental Shelf from Long Island to George’s Bank (east of Massachusetts), SSTs are approaching 4 C above normal (they are presently or have been approximately 10-15 C rather than 6-11 C). This anomalous event presumably results in significant changes in the distribution and types of fish and other food available for foraging; this is exactly the type of environmental change that would fuel long-range dispersal such as that being seen in Florida right now.

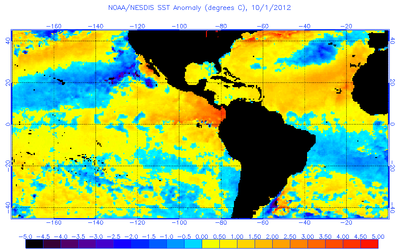

Fig. 6. Sea Surface Temperature (SST) anomaly from October 2012. The red area off Atlantic Canada and the Northeast coast indicates unusually warm water there, which probably has been driving this invasion.

Fig. 7. Sea Surface Temperature anomaly from November 2012. In this image the SST anomaly off the Northeast coast appears even stronger, while waters off Florida and the Southeast coast have been comparatively cool relative to normal.

Fig. 8. Sea Surface Temperature anomaly from December 2012. This image is most relevant to the current invasion, and shows that the SST anomaly off the Northeast has continued into November and early December, which are the months when most Razorbills move into waters off New England and Atlantic Canada. Presumably these birds dd not find appropriate food in these waters and continued moving.

Concurrently, SSTs in Florida are abnormally cold, which may result in better than average foraging for Razorbills along the Florida coast. While the birds that have strayed this far south are sure to be food-stressed and may not survive the winter in these nearly tropical waters, the cooler temperatures may mean that these birds stand a better chance of survival than in other years, since the cooler, more productive waters may provide more small fish for them to feed on. This may result in more Razorbills hanging out in productive locations, rather than continuing to move on in search of food resources that they may never find. With luck, birders can continue to document this remarkable phenomenon well into 2013.

What actually has caused this SST anomaly is unclear to us at this point, and we would welcome authoritative articles on the topic if anyone is aware of them. Obviously, oceans have large cycles of warming and cooling (e.g., El Niño and La Niña events), but long-term climate change and shifts in ocean currents and upwelling patterns and changing salinity gradients are also part of the equation.

One interesting thing to note is that while this is especially pronounced now, the warmer than-average ocean temperatures has been a theme of most of 2012 in this region. See this article from NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Center, which states that SST for the first half of 2012 were the highest ever on record for the Northeast US. In retrospect, that event from last winter may have explained some of the historically high Razorbill counts off of Georgia on pelagic trips last, including this nice illustrated checklist with 43 from 15 Jan 2012!

Razorbills and other low Arctic alcids (especially Common Murre and Atlantic Puffin) have actually enjoyed increasing populations in recent years due to hard work of conservationists protecting their nesting islands, and due to long term recoveries from over-hunting/egging of the past. Additionally, increases in some Razorbill populations in Arctic Canada may actually relate to these warmer spring and summer waters that allow some favored prey items to expand farther North and East (Gaston and Woo 2008). Given these big increases in the population of Razorbill may be a big part of why this is happening this year and has never happened at this scale in the past. Historically high populations plus a major SST anomaly upheaval seem to be the factors that have combined this year to create this unprecedented event.

Final thoughts

Although this is certainly exciting for Florida and Gulf coast birders, it is difficult to view this as good news for the birds. Razorbills and the other species invading Florida have adapted over millions of years to feed on a certain assemblage of sea life in a range of sea surface temperatures. If the marine system starts changing rapidly and quickly becomes something unfamiliar to Razorbills and other species, it may have profound impacts on their populations.

Perhaps the recent Razorbill invasion should be viewed simultaneously as an exciting chance to see these remarkable birds in Florida and document an unprecedented invasion, while at the same time recognizing that it probably signals birds making desperate attempts to flee a home that suddenly became unfamiliar and inhospitable. Moreover, there is the question of whether the 2012 invasion is an anomaly or marks the beginning of a frightening trend.

References

Gaston, A. J. and K. Woo. 2008. Razorbills (Alca torda) follow subarctic prey into the Canadian Arctic: colonization results from climate change?Auk 125(4):939-942.

Lavers, Jennifer, Mark Hipfner, Gilles Chapdelaine and J. Mark Hipfner. 2009. Razorbill (Alcatorda), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/635

doi:10.2173/bna.635

Lilliendahl, K. 2009. Winter diets of auks in Icelandic coastal waters. Marine Biology Research 5: 143-154.

————————————————————-

Posted by Marshall Iliff (Team eBird), Andy Farnsworth (Team BirdCast), and Tom Johnson, with editorial comments by Brian Sullivan (Team eBird), Matt Hafner, Tom Reed, Tony Diamond, and several others.

Fig. 9. Flock of Razorbills off Boynton Beach Inlet, Palm Beach Co., FL, part of some 200 counted on this 15 Dec 2012 checklist. Photo courtesy of Rick Schofield.