November 2012 is shaping up to be an historic month. There could be more bird species east of the Mississippi this November than any other on record. Several factors are responsible for this: conditions for western vagrancy are good with more excitement to come; Hurricane Sandy’s shakeup left a fascinating bird load in many areas in early November and some of those effects are still worth watching; and of course, we have a major finch irruption year on our hands. Below we highlight these patterns and we hope eBirders will get out there and help to document their effects and emerging patterns.

Cave Swallows: already in East, and more coming (and even more after that!)

The first November Cave Swallows in the East were discovered in 1992 at Cape May, NJ, and amazingly, the species has been found almost annually since. Initially this phenomenon was almost restricted to Cape May, but soon other migrant traps got in on the Cave Swallow action: Point Pelee and Long Point in Ontario, Long Island, NY, and Lighthouse Point, CT, and Lake Ontario hotspots like Hamlin Beach SP. The year 1999 saw one of the biggest movements, with literally hundreds found. In the years since, Cave Swallows straying east from late October to mid-December (mostly in November) has been expected, provided the right weather.

The right weather is basically strong southerlies or southwesterlies in the late October to late November period. These southwestern winds often occur in advance of long trailing cold fronts (those blue jagged lines on weather maps). On the days of the southwesterlies, large numbers of Cave Swallows can sometimes be seen at “spring migration” hotspots, such as those along the southern Lake Ontario shoreline (e.g., Hamlin Beach SP). The swallows moving north with these warm winds gather along the lake shore, not wanting to get pushed offshore. As the cold front passes, winds come around to the northwest–it is on those winds that Cave Swallows are seen at Cape May, Long Island, New England coast, and other “fall migration” hotspots. It takes both elements to get Cave Swallows to the East Coast. In almost all recent years, at least a couple fronts have brought numbers of Cave Swallows. Once present, it seems that these swallows can bounce around.

The weather pattern in advance of Hurricane Sandy provided perfect conditions to bring Cave Swallows into the region, and brought large numbers of Cave Swallows to the Great Lakes: check out the 156 from Hamlin Beach SP on 25 Oct or the 148 from Ontario on 26 Oct! With Sandy‘s arrival, the low to the northwest interacted with Sandy to bring Cave Swallows right into the storm. On the day of the storm, a number of Cave Swallows were seen in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and elsewhere, and in the days following Sandy‘s clearing (after winds switched to the northwest), those same Cave Swallows likely concentrated on the coast of Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New Jersey.

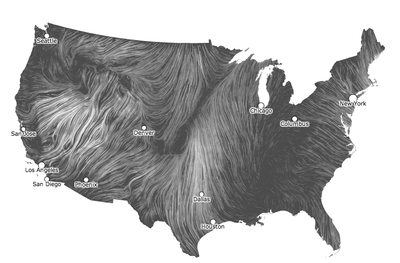

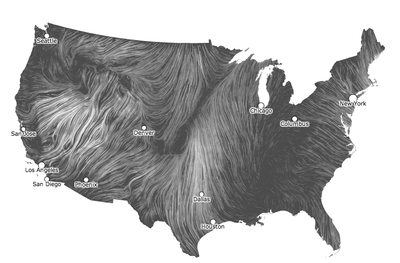

Winds this week are probably pushing another pulse of Cave Swallows into the Great Lakes area. Next week, as the remnants of Winter Storm Brutus move east the conditions should be even better for a major arrival of Cave Swallows. For those watching for this always-exciting-vagrant, the below figure is a nice site worth bookmarking.

Fig. 1. The wind map above from 3pm 8 November is available animated in real-time here and is a superb way to envision potential movement. The wind field streaming north from central Texas (strongest through Dallas) is showing surface speeds of 20 mph or so and this will surely push some Cave Swallows into the Great Lakes and then east from there. When these same southwesterlies hit the Lake Erie and Lake Ontario shoreline this weekend, Cave Swallows can be expected. Furthermore, a frontal passage early next week means that these birds should appear in coastal areas by mid-week.

Cave Swallow as an indicator species–watch for other November vagrants!

When Cave Swallows arrive, it is probably fair to think of them as a conspicuous indicator of a vagrancy event. Other species with the same general source regin (Texas and northern Mexico) are likely to be transported similarly in the same conditions, albeit not in flocks and not in comparable numbers. Ash-throated Flycatcher is perhaps on of the more regular such species, so birders should be on high alert for them in these next few weeks as well. One in

Massachusetts last weekend was the first of the fall on the East Coast, but more should follow. A couple “Audubon’s” Yellow-rumped Warblers have appeared in Massachusetts and Nova Scotia and several Western Kingbirds have been around as well. Other birds to think about if there are lots of Cave Swallows next week are things like Townsend’s, Black-throated Gray, and MacGillivray’s Warblers, Western Tanager, Franklin’s Gull, Bell’s Vireo, Say’s Phoebe and more. Long shot possibilities include Sage Thrasher, Tropical or Cassin’s Kingbird (The

first for Minnesota was recently found), western

Empidonax (Hammond’s, Dusky, Gray, or Pacific-slope/Cordilleran). When Cave Swallow reports start to increase in your area, be aware that there may be some rare birds hiding in the bushes too!

Fig. 2. Ash-throated Flycatcher at Squaw Rock Park, near Boston, MA, 5 Nov 2012. This is one of the other “indicator species” along with Cave Swallow, that November western vagrancy is under way!

Lingering Effects of Hurricane Sandy

Hurricane Sandy and the associated North Atlantic high pressure and Great Lakes low pressure system really did shake up the birds in the eastern United States, much like one of those little snowglobes. Pelagic birds were inland, overland migrant waterfowl were grounded, Arctic birds were south, western birds made it east, and some European birds even crossed the ocean. We are planning an analysis story about this colossal storm and its effects on birds. In the near term suffice to say some of Sandy’s shakeup may still be visible in the Northeastern avifauna and includes some interesting birds that you could find in your area. Below are two to think about.

Northern Lapwings!

Six confirmed

Northern Lapwing reports from Massachusetts (3), Maine, New Jersey, and Newfoundland are surely indicative of a pattern that had been shaping up for the past 2-3 weeks. Strong easterly winds over the North Atlantic are likely responsible not only for driving

Sandy ashore in New Jersey (rather than allowing it to travel the same route as

Wilma in 2005) but also for transporting lapwings from Europe to North America. Please visit the

BirdCast site for a much more detailed account on how this probably happened!

In the meantime, now that lapwings are here, they will probably float around the Northeast for a while and may surprise you at a local agricultural field, golf course, turf farm, or pasture. Anywhere that Killdeer occur in the East should be checked for Northern Lapwing this fall and winter. The species has successfully wintered in several East Coast states, so the lapwings that arrived last week might still be around in March!

Addenda 13 Nov 2012: News of at least six more Northern Lapwings buzzed across birding hotlines (and eBird Alerts) this weekend: In Nova Scotia, one was photographed in Shelburne Co. on 11 Nov and on Long Island, NY, one was photographed at Robert Moses SP on 8 Nov and two popped up at Deep Hollow Ranch, Montauk, 10-11 Nov. In addition, one at the Cumberland Farms fields in Middleboro, MA, appeared 11 Nov and was enjoyed by many while another appeared nearby on 12 Nov! Surely there are more out there, so be sure to check likely spots near you!

Fig. 3. Northern Lapwing in Allentown, Mercer Co., NJ, on 8 Nov 2012. See the eBird checklist from shocked eBird reviewer Sam Galick

here.

Slingshot Passerines

The days after Hurricane

Sandy’s landfall saw the appearance of a suite of unseasonably weird Neotropical migrants from New Jersey north to Maine and inland to Ontario. It is likely that this array of migrants, including Eastern Wood-Pewee, Northern Parula, Bay-breasted Warbler, Magnolia Warbler, Indigo Bunting, and several others were migrating between the US and the Greater Antilles en route to Central and South America when they were “sucked in” to the massive circulation around

Sandy. Check the

Birdcast site for more details.

Winter Finch Superflight!

Matt Young provided a look at what is going on with winter finches and characterizes this year as a “superflight”, with essentially all finch species on the move or soon to be on the move.

From Matt: The last superflight in the East occurred in 1997-98, and what is even more exciting about this year’s movement is that it includes finches in both the West and the East.

So far we’ve already seen large movements of

Pine Siskin, Red Crossbill and

Red-breasted Nuthatch (an honorary finch) on both coasts. All three have shown up farther south than typical. Red-breasted Nuthatches have been reported in central Florida and throughout the Gulf Coast states. Pine Siskins have smashed records at several sites including Hawk Ridge, Minnesota and Cape May, New Jersey. A flight on Long Island on 21 October yielded an amazing estimate of 20,000 siskins.

Purple Finches are already being reported well into the Southern Appalachians.

Evening Grosbeaks, that favorite feeder bird from yesteryear, looks to be making its largest eastward push since 1997-98. In recent years Evening Grosbeaks haven’t appeared in Pennsylvania or Connecticut until November and December, with scarcely any even then, but this year made their first appearances at the end of September. Evening Grosbeaks have already reached Maryland, West Virginia and Delaware, and some should be expected into the Carolinas and perhaps the mountains of Georgia this year.

After an unprecedented

Red Crossbill flight that materialized in August across the Northern Tier States, crossbills look to be on the move again. In the last two weeks both Red and White-winged Crossbills have been reported nearly daily at Whitefish Point in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and at Hawk Ridge in Minnesota. Migrating Red Crossbills have also been reported several times in recent weeks at Hawk Mountain in Pennsylvania, with others in Massachusetts. As was true earlier in the fall, nearly all of the recordings received have been

Type 3 (see more on crossbill types

here). People in the Southern Appalachian States should be on the lookout for Type 3 (and any other crossbill type), which has only one record to date for North Carolina.

White-winged Crossbill has hit the East in force in the past few days, with early November reports en masse from Maine to Rhode Island and the vanguard reaching as far south as Maryland. Type 2 Red Crossbills appear to be moving from the Rockies onto the Great Plains. They have been documented with audio recordings as far east as Illinois and Missouri during the first week of November.

As we now head into late October, early reports strongly suggest Bohemian Waxwing (another honorary finch), Pine Grosbeak and redpolls are on their way too. Bohemians have been reported in several Northeastern states, Pine Grosbeak in Massachusetts and redpolls in Connecticut, and it’s still only early November. Look for redpolls at New York feeders by the end of November. With the heat and drought of the past summer, it looks like this year could be a very interesting winter for finches across much of the country. As discussed in my crossbill piece, there are two things to expect: 1) because there’s a lack of natural food across large sections of the continent, it could be an amazing year at feeders, and 2) the Mid-Atlantic States (and perhaps Carolinas) could experience a superflight not seen in 15 years!

Stealth migrants and the importance of reporting common birds

Detecting movements of “resident” species is much more challenging. One of the best ways of doing this is to make repeated counts from a single area. Understanding the full scope and magnitude of these movements requires observations from throughout a species range. Looking at eBird records, it appears that a stealth movement of Black-capped Chickadees may already be underway. Apparently migratory flocks have been noted in portions of the Great Lakes and New York. Observers should watch carefully for this species south of range.