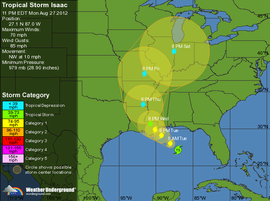

Predicted path of Isaac. Map courtesy of Weather Underground.

Last year, Team eBird posted a primer on hurricane birding. With the 2012 hurricane season already nearly 2.5 months old, and several recent tropical systems marching across oceans, we suggest that it is worthwhile to review this article and get prepared to find birds in the wake of any storms that make landfall. Birders in the central Gulf Coast states and those states in the Mississippi River valley may want to review this posting very closely, given the current forecast path for Tropical Storm Isaac for 28-31 August!

Those of you with an eye for hurricane birding are probably aware that Tropical Storm Isaac is forecast to become a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico. Landfall is projected in southeastern Louisiana during the early hours of Wednesday morning. The Mississippi River delta appears to be square in the cross hairs of this storm, its movement forecast to continue inland up the Mississippi River valley as a Tropical Storm through Thursday before becoming a Tropical depression by Friday in Arkansas and eventually moving up toward the Great Lakes region on Saturday.

Birding interests in the New Orleans and southeastern Louisiana region should probably seek shelter or evacuate rather than considering birding, given what looks like a nasty and perhaps dangerous mess, and presumably much flooding as the storm passes through the area. For those people that are safely hunkered down in the storm’s impact zone, the New Orleans and Slidell areas should see numbers of Sooty and Bridled Terns, with a chance, perhaps, for Brown and even Black Noddies. Previous storms with similar tracks have also produced large Magnificent Frigatebird deposits in the lower Mississippi, so birders should watch for such concentrations. Several bodies of water are probably worth regular checks if conditions are safe, including Lake Ponchartrain and Barnett Reservoir; based on previous observers’ experiences, the time to do this is as the storm is passing or within whatever daylight hours remain on the same day the storm passes.

Birders along the immediate Gulf coast east to the AL/FL border are likely to see entrained and displaced birds. Birders should pay particular attention to terns, as the likelihood of tropical terns and noddies is high. Additionally, concentrations of more common species are likely, and these concentrations should be checked for tropical waifs. In addition, Audubon’s Shearwater, Band-rumped Storm-Petrel, and possibly White-tailed Tropicbird could be seen from shore.

As the system moves inland, this storms seems ripe for carrying tropical terns and other associated waifs inland onto large bodies of water. Given the slow speed forecast for the remnants of the storm once it makes landfall, most avian deposits seem likely to occur in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas. Birders in these areas should definitely watch large bodies of water and generally look up constantly once the storm has passed – reorienting displaced birds could be moving almost any direction to get back to large river systems to take them to the Gulf of Mexico.

Four lakes in northwestern Mississippi appear to be very well-situated along the northeast quadrant of the storm and have high dams and/or nearby parks that may allow safe (and even sheltered?) viewing. If you are nearby and can do so safely, consider a check of Grenada Lake, Enid Lake, Sardis Lake, and Arkabutla Lake. If you cannot safely visit during the storm, checking these lakes as soon as possible after the storm could be a good strategy. The southwest points of the lakes may be best as displaced birds try to get back to the Gulf of Mexico or to the Mississippi River, but of course, wind at the time may have a great effect on where birds concentrate on those lakes.

Following this line of thought, birders that can safely observe the Mississippi River are likely to see many birds using the river system as a conduit to return to the ocean. Be aware however that the dangers of severe flooding are very serious with this storm and please do not take any chances at all in your pursuit of birds. With safety first in mind, but those that can get out may see returning tropical terns, jaegers, frigatebirds and possibly entrained Band-rumped Storm-Petrels. Again, please remember that birding around rivers and streams in times of heavy rain may be extremely dangerous, with changing water levels occurring unpredictably and rapidly. Be safe.

Additionally, birders should pay close attention to swifts and swallows, as the potential for an interesting deposit of these species exists. In particular, watch for Cave Swallows, Caribbean Martin, and Black Swift, and have your cameras ready! Caribbean Martin and “Caribbbean” Black Swift have yet to be unequivocally documented in the United States.

As the depression moves farther north, we expect only a handful of Sooty Terns to be deposited far afield inland. However, this system could bring frigatebirds much farther inland than most other species, given their aerial abilities, so birders should be watchful for soaring frigatebirds perhaps even into the Great Lakes.

We have mentioned previously that other species may be “knocked down” by tropical systems, rather than entrained or displaced. Birders should watch for shorebird and gull fallouts in areas of precipitation and instability associated with the storm’s passage. Inland jaegers, Sabine’s Gull, Arctic Tern, phalaropes, and numerous shorebirds, all of which may be high altitude migrants, may be forced to land in appropriate habitat (or inappropriate habitat) as the remnants of Isaac pass.

Finally, once a tropical system passes, the nights that follow typically bring northerly and westerly winds. Those of you dialed into watching diurnal movements should watch for these to begin as soon as the winds shift. Those of you tuned to flight calls of nocturnally migrating birds should consider some nocturnal listening once Isaac passes.

We cannot overemphasize the importance of safety first and shelter. PLEASE be smart, and reread these tips, and exercise safety first, above all else! We included our original messages about safety and about how to bird these systems below.

HURRICANE BIRDING — AN eBIRD PRIMER

SAFETY FIRST !!!

To reiterate, remember that hurricanes are devastating and dangerous events. Driving in rain is bad enough, but driving in rain and hurricane force winds can be deadly. Avoid crossing bridges in high winds. Downed trees and powerlines, blowing debris, and other drivers only add to the peril.

Storm surge flooding is perhaps the most dangerous aspects of such storms. Since a surge of 15 ft or more can occur, many otherwise “safe” areas might be deadly in a hurricane. Do not take any chances with driving through flooded areas and do not do anything that might trap you in a low-lying area that is being flooded.

If you are considering looking for birds before or after the storm, make sure you are being safe during the storm’s passage. Don’t even consider intentionally putting yourself in the center of the strongest part of the storm.

SHELTER

Whether birding in the advancing storm or after the passage of the storm, you will need shelter from both wind and rain. If you plan any birding in the storm, think hard about what sites (overhangs on buildings, hotels with rooms facing the lake, river, or ocean, etc.) will provide shelter for you and your optics and not be facing directly into the expected wind direction. Birding from your car can sometimes be effective and safe, since an open car window facing away from the wind can be quite effective. Think in advance about how to use your telescope, either on a tripod or a window mount, from inside your car. Bring paper towels to dry off wet optics!

WEATHER

Understanding hurricanes is important. Hurricanes are cyclonic, so the winds are rotating counter-clockwise in the northern hemisphere. This means that northeast quadrant of an advancing storm will have winds from the southeast, and that those winds will shift to become southwesterly as the storm center passes to the west. This is important to understand since seabirds that do not like to fly over land may be ‘pinned’ against shorelines in the high winds of a hurricane. As the storm passes, you may want to shift your strategy, and be sure to consider shifting winds as you do so. Also remember that the northeastern quadrant of the storm has the strongest and most dangerous winds as well as the most rain. After the storm passes, conditions can quickly clear up and visibility can be excellent.

BIRDS IN THE STORM

One important general pattern is that the eastern sides of hurricanes tend to have higher loads of displaced birds than the western side. This could be because the tighter isobars here keep birds more effectively entrained within the storm. But note that in Hurricane Bob most rarities in New England were along the path of the eye.

Numerous reports also refer to birds being ‘trapped’ within the eye of storms, and many observers have seen large numbers of rarities in the calm eye of storms, although we would NEVER recommend intentionally putting yourself in the path of a hurricane with a well-defined eye (these tend to be stronger storms).

One consideration is how birds will behave in relation to obstructions. Most displaced birds will want to stay over water if possible, but tubenoses may be more closely tied to water than terns, for example. At a given reservoir a shearwater, storm-petrel, or even Pterodroma petrel is likely to stay for the day, maybe departing overnight. But terns, gulls, and shorebirds may depart if the weather allows; your exciting Sooty Tern may pick up and fly over the treeline and away. Note also that certain seabirds, especially boobies and gannets, shearwaters, and Pterodroma petrels, seem to avoid crossing bridges. There are several indications that birds like this may feel ‘trapped’ on a given side of a bridge. This could be a factor as you plan where to check for birds.

Hurricane strength obviously has a bearing on how many birds are displaced, and roughly speaking, stronger storms carry more birds than weaker ones. However, strong hurricanes that dissipate to Tropical Storms can still carry birds long distances, ESPECIALLY if that dissipation occurs after the storm makes landfall. Storms that weaken to Tropical Storms while still at sea typically carry surprisingly few displaced seabirds.

SITES TO LOOK FOR BIRDS

Before the storm

An advancing hurricane will have a large front of winds blowing from the southeast in its northeast quadrant. If birding before the storm, pick a site where southeasterly winds will pin birds against the shoreline, or better yet, concentrate them in a bay or river mouth. Watch for storm birds flying from south to north with the winds at their backs. Often the local birds may be flying any which way, but the interesting storm birds will be heading up from the south fleeing the path of the encroaching storm. Sometimes rarities like Sooty Terns can fall out at inland lakes with the storm center still many hundreds of miles to the south. For example, Sooty Terns turned up at an inland lake in Maryland at 2pm on Friday, 6 September 1996, while the storm center of Hurricane Fran was still south of Cape Hatteras. It pays to get out and try, but do so safely and beware the storm surge and encroaching storm.

During the storm

Birds can be anywhere. Check any spot with water, especially rivers, large lakes, or inland bays. even small lakes, ponds, or wet fields can generate exciting birds, especially shorebirds. If you can’t get to water, just look up. Some lucky birders have picked up Sooty Terns and other surprises right over city rooftops with no water in sight! Try to get a look at any grounded bird that a friend or relative reports to you and make contact with rehab centers that might receive and rehabilitate rare birds.

After the storm

It can often be difficult to connect with displaced seabirds after the passage of the storm. Check lakes for rare seabirds that may feel “trapped” on the lake until nightfall. Check rivers and coastal bays for birds reorienting back to saltwater, especially the eastern sides if westerly winds are ‘pinning’ birds to a given shoreline. Theoretically, there could be several days worth of commuting rare birds along major rivers like the Hudson, Delaware, and Connecticut Rivers.

Be alert for any sick, dead, or dying birds, since these could represent rarities. Check known shorebird spots, tern concentration spots, gull roosts, etc to see if any rarities have stopped for a rest. Bays behind barrier islands can often trap seabirds just after a storm, and often the seabirds will also feel trapped by bridges. If there is a route back to the ocean, they may eventually find it, but many tubenoses (e.g., shearwaters and storm-petrels) might feel ‘stuck’ in a barrier island bay even if the ocean is just 200m away if they simply flew over the narrow strip of land.

Usually most rarities occur within a few hours or at most a day of the storm’s passage. Only on very rare occasion do species like Sooty Terns or tubenoses occur longer than 24 hours after a storms passage, and many seem to leave overnight. Very large lakes, especially the Great Lakes, can sometimes hold rarities for up to a week though, so be sure to get out birding as much as you can after a storm and see what is about. Frigatebirds in particular are famous for occurring well before and well after storm passage.