Most of the time when you see a raven, its size is hard to appreciate because there’s not much there for context. Usually, it’s somewhat distant and, more often than not, flying. But ravens are enormous, and their size is quickly appreciated if you have the opportunity to see them next to a bird like an eagle or a crow.

In eastern North America, raven populations declined tremendously during the 19th century. Declines were so steep that multiple states expressly stated in the 20s and 30s that extirpation was a distinct possibility. Writers in West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and even Minnesota all warned of pending local extinction, and it’s possible that ravens were briefly absent from Maryland’s breeding avifauna. Garrett and Allegany counties had reports of raven nests in the late 1800s, but the next nest wasn’t reported until the 1930s. The entire eastern population of ravens appeared to undergo a synchronous decline and then a subsequent expansion beginning in the 1950s.

Common Raven are large birds, but their size doesn’t always come across. This figure compares Bald Eagle (back silhouette), Common Raven (middle white silhouette), and American Crow (front silhouette). The median wingspan provided in the respective birdsoftheworld.org species account was used as the comparison value (Bald Eagle, 81 in; Common Raven, 53 in; American Crow, 33 in).

Declines appear to have been due to a combination of habitat loss—particularly logging—and shooting, trapping, and poisoned baits. As forest regrew and matured and predator persecution decreased, it seems ravens were able to reclaim parts of their former range. Food availability may also restrict their density in a region, and its unclear how competition with crows, vultures, and eagles may be impacting their distribution. Regardless, across eastern North America they are continuing a decades-long reclamation of their range. Their use of human-made nest sites in the Piedmont—as BBA2 coordinator Walter Ellison correctly predicted—is allowing them to expand into parts of the state they have never been documented nesting in before.

Top Tips

- Record the direction they’re flying

- Check communications towers and large light poles for nests

- Be mindful of non-breeding floaters

Habitat

Ravens are most common in western Maryland, but since BBA2 they have become increasingly common in the Piedmont and sightings south of there are not scarce. In fact, a nest in Charles County represents the first raven documented breeding in Maryland’s Coastal Plain, and recurring sightings of a raven in Chestertown could eventually result in an Eastern Shore nest.

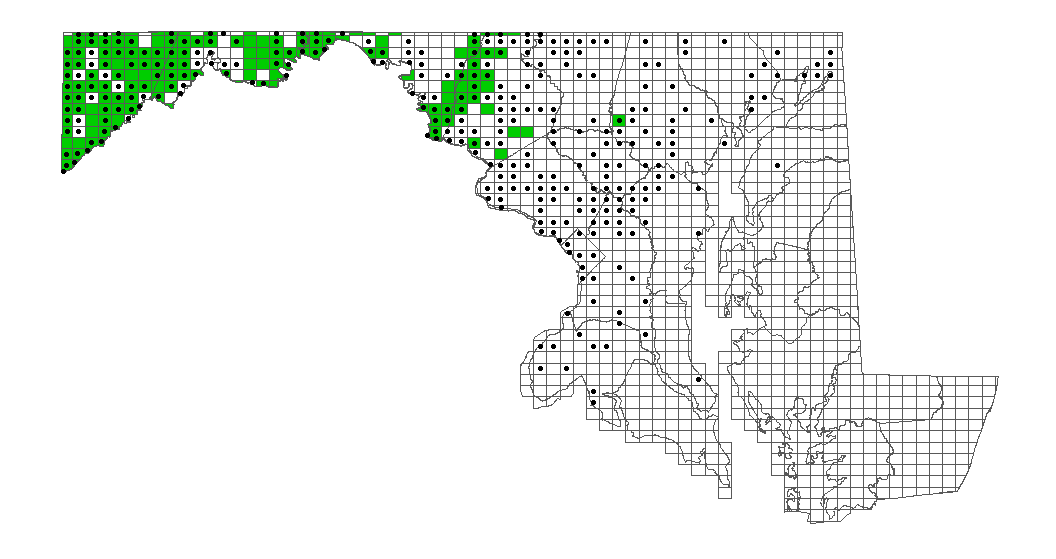

Common Raven breeding distribution map from the Maryland & DC Breeding Bird Atlas 2 (2002–2006) and Atlas 3 (2020–2022). Green fill indicates a BBA2 Common Raven breeding observation in that block, while black dots represent coded BBA3 observations.

Common Ravens will nest in cliffs, trees, large light poles, communications towers, bridges, and the like. When nesting in cliffs, they almost always select a location with an overhang, preferably facing south or west. Conifers are preferred when nesting in trees; usually the nest is in a crotch near the top with some overhanging cover. Young ravens are messy and will defecate over the edge of the nest after they are a couple of weeks old. The whitewash can show up well, depending on the nest site substrate. Nests apparently build up quite an odor as well, but atlasing by scent is still a rather undeveloped technique.

Pairs maintain a territory throughout the year, and the size of their territory appears to be related to food availability. In places where territory size has been measured, it varies hugely, from 15 mi2 in Minnesota to 0.6 mi2 in California. In Virginia, nests were reported to be regularly spaced about every 6 km. There, more sites were available than pairs, indicating nest site availability was not the limiting factor for local raven density.

Identification

Common Ravens are fairly straightforward to identify as a corvid—they’re a large black bird. But separating ravens from crows can be a bit trickier, particularly if they are silent. A raven’s tail is more wedge-shaped than a crow’s fan-shaped tail. Ravens glide and soar more than crows do, and they are more acrobatic in the air—including doing barrel rolls! If you have a closer view of a raven, the heavy bill is noticeable and the bill’s base is covered by feathers. Raven’s throats also have hackles that crows lack.

Behavior and Phenology

Common Ravens are permanent residents, although ravens don’t nest until 2–4 years of age and these non-breeding birds wander widely. Raven pairs begin laying an average of five eggs early in the year. In 2021, a Virginia pair laid their first egg on January 1. Nest building begins the week before egg-laying. Ravens will re-use nest sites, but they may have multiple sites to pick from within their territory. Incubation lasts 20–25 days, and the blue-eyed juveniles fledge 5–7 weeks later. Fledglings appear to remain on the natal territory for a few more weeks before leaving to form flocks with other juveniles.

Late December–March: Courtship, pair formation, nest building, egg laying

March–May: Incubation, fledglings

May–July: Fledglings, feeding young

Breeding Codes

Ravens are most easily detected by voice and they are often seen flying fairly high. Their home range can cover multiple blocks and they can travel quite far to forage. It’s worth noting the direction a raven is flying in during the first half of the year; these comments may help triangulate a potential nest location. The male feeds the female and both feed the chicks, so—like most birds—males make frequent trips to the nest during the breeding season.

Raven pairs will defend their nest site from potential threats, but they may also exhibit less aggressive, more evasive behavior. One Oregon study found that in areas with a lower human population, ravens were more likely to be aggressive towards humans in their nest defense. Conversely, ravens that lived near more people were more likely to leave the nest site quietly, presumably to avoid attracting attention to the nest. Regardless of their response around humans, ravens will often attack hawks and crows perceived to be a threat, and seeing this aggression is an indication that the nest site is likely quite close by.

Juveniles have a pink-lined mouth, while adults’ mouths are all black. The chicks’ raspy begging calls are loud, and can reportedly be heard from up to a mile away.

Habitat: Ravens can travel far from the nest site during the breeding season, but a raven in an area with a potential nest site nearby is a suitable candidate for code H (habitat).

Singing: Their complex, varied vocalizations are not considered songs, and singing codes (S, S7, and M) should not be applied.

Pairs: Two adults acting cohesively can be considered a pair (code P), but birds calling at or near each other may be territorial rivals so use caution when interpreting raven interactions.

Territorial: Pairs will defend their territory against intruders and chases of these intruders can extend for miles.

Courtship: Displays occur throughout the year and include aerial acrobatics as well as bowing, fluffing, bill-snapping, and preening each other.

Probable nest site: Visits—especially repeated visits—to a reasonable nest site, such as a stand of conifers or a cliff, should receive code N (visiting a probable nest site).

Agitation: Chasing hawks, crows, or even vultures should receive code A (agitated bird).

Nest construction: Code CN (carrying nest material) should be used when a raven is seen flying with sticks, grasses, or other nest construction materials. When you see a raven at the nest site building the nest, use code NB (nest building).

Used nest: A classic raven nest is a large stick nest (15–60 in wide) under a cliff overhang surrounded by whitewash. Be careful not to confuse nests on other structures with Osprey or eagle nests, and be especially cautious with nests built in trees. To get an idea of what a raven nest looks like, check out these images on Macaulay Library.

Active nest: A nest with an adult on it should be coded ON (occupied nest), unless you are very fortunate and can see eggs (code NE) or, later in the breeding season, you can see the chicks in the nest (code NY).

Young: Family groups will exist for several weeks, and can be coded as Recently Fledged Young (code FL). If an adult feeds one of these fledged birds, it should be coded as Feeding Young (code FY).

Carrying food: Ravens will carry food back to their nest, but like other corvids, will also carry food to eat undisturbed. If you suspect a raven carrying food is heading to a nest, it’s perfectly acceptable to use the CF code—just provide an explanation in the comments section about why you used that code.

If you’re interested in learning more about ravens, corvid expert Dr. John Marzluff has a talk recorded on YouTube about relationships that ravens have with people and other wildlife.

References

Ellison, W.G. 2010. 2nd Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Maryland and the District of Columbia. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore. 494 p.

Harlow, R.C. 1922. The Breeding Habits of the Northern Raven in Pennsylvania. The Auk. 39(3). 399-410.

Hooper, R.G. 1977. Nesting Habitat of Common Ravens in Virginia. The Wilson Bulletin. 89(2). 233-242.

Jones, F.M. 1935. Nesting of the Raven in Virginia. The Wilson Bulletin. 47(3). 188-191.

Knight, R.L. 1984. Responses of Nesting Ravens to People in Areas of Different Human Densities. The Condor. 86. 345-346.

Pfannmuller, L., G. Niemi, J. Green, B. Sample, N. Walton, E. Zlonis, T. Brown, A. Bracey, G. Host, J. Reed, K. Rewinkel, and N. Will. 2017. The First Minnesota Breeding Bird Atlas (2009-2013).

Robbins, C.S. 1996. Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Maryland and the District of Columbia. University of Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh. 479 p.

Stewart, R.E. and C.S. Robbins. 1958. Birds of Maryland and the District of Columbia. United States Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Woodward, J. and P. Woodward. 2021. Nesting of Common Ravens (Corvus corax) in the Eastern Piedmont of Virginia, Fairfax City Area 2018–2021. The Raven. 92. 10-14.